The Project Gutenberg EBook of The King's Warrant, by Alfred H. Engelbach

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The King's Warrant

A Story of Old and New France

Author: Alfred H. Engelbach

Release Date: December 12, 2008 [EBook #27508]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE KING'S WARRANT ***

Produced by Al Haines

t last England and France had formally drawn the sword which they had sheathed only eight years before at the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, and the great struggle known in history as the Seven Years' War had begun in earnest. Yet although the old countries had until now managed to abstain from a declared and open rupture in the Old World, it had for well-nigh two years past been far otherwise with their great dependencies beyond the Atlantic. There, during the years 1754 and 1755, New France and New England had already been carrying on a deadly conflict, which seemed to increase in intensity and fierceness as the months rolled on, and in which for some time the royal troops of both kingdoms had taken a prominent part, notwithstanding the nominal state of peace between the mother countries. Some short-sighted men, indeed, tried to persuade themselves of the possibility that the colonists might carry on the war on the soil of the New World, without necessarily compromising the peace of Europe; but the European powers had their own apples of discord, and the ambitious designs of the Great Frederick had now set Europe once more in a blaze.

But what was to be the issue of the struggle in America? With the history of the last hundred years open before us—with such names as those of Wolfe, Abercrombie, and Wellington; Rodney, Howe, and Nelson ever ringing now like household words in our ears—with such achievements as those of the plains of Abraham, the sand-hills of Aboukir, Waterloo, the Nile and Trafalgar ever present to our minds, we are apt enough to ignore the uncertainty which, humanly speaking, in those days hung about the result of a collision between New England and New France, backed by the power of their respective sovereign states. From the descendants of the Pilgrim Fathers might, indeed, be expected an amount of vigour, energy, and self-reliance, that must needs contribute greatly to success in such a contest; but these very qualities, so far from finding much favour with their rulers in the Old Country, were like enough to be met with jealousy and distrust, to produce coldness and estrangement, and perhaps even to weaken the support of the government in England. In addition to this, the rivalries and dissensions that were always springing up amongst the several colonies themselves could hardly fail to interfere materially, as they had done for years past, with their cordial combination in any effort, however needful, for their common good. Canada, on the other hand, was essentially the creation of the parent State, its favoured offspring; it was unceasingly cherished and fostered as a nursery of commerce, and as the means of planting the Christian faith amongst the heathens, over which France would spread her protecting wings with the jealousy of an eagle defending its young even at the cost of its life. Yet so far as the colony was concerned that protection had been dearly bought at a cost of patronage and favouritism that had checked all healthy exertion amongst the colonists. With some bright exceptions, oppression, rapacity, and bigotry had ever characterised the ruling powers in the colony, and now that the hour of trial had come there could be little hope that the colonists of New France, however loyally disposed, could do much to help King Louis to retain this much-prized dependency of the French crown. But what of that? The French king probably cared as little for the help of his Canadian subjects as he did for the enmity of the New Englanders. Nearly fifty years had passed away since the victories of Marlborough, whilst the humiliation of Dettingen had been eclipsed by the triumph of Fontenoy. England, moreover, had but just succeeded, with no little difficulty, in putting down a rebellion at home, and Jacobite disaffection was still rife in the land—such at least might well be the French view of the English situation. In America, too, the successes of General Johnson on Lake Champlain, however substantial, could not efface the recollection of Braddock's disastrous rout at Fort Duquesne.

There were, nevertheless, some circumstances in the case which led reflecting men to think that even were the troops of France commanded by another Marshal Saxe the victory might yet be doubtful. The exploits of Anson, Hawke, Boscawen, and Warren, both previously to the peace, and now again immediately on the resumption of hostilities, had established almost beyond question England's superiority at sea, and this could scarcely fail to be of incalculable advantage in a contest which would make it necessary to transport and convey land forces to a distant theatre of war. There was, moreover, yet another circumstance that could not be put out of sight, even by those most inclined to rely on the military prestige of France, acquired in wars of the old conventional European type. Brought year by year more and more into contact with the white man, and year by year more debased by an insatiable thirst for the deadly fire-water, the American Indian had indeed gradually become less and less formidable to his foes; he was, however, by no means an enemy to be despised. Many a well-conceived plan was defeated by the sudden and murderous onslaught of a tribe whose stealthy approach had eluded all common precautions, and many an engagement which in civilised war might have had but small results, was turned into a massacre from which not one escaped to tell the tale. Even the hardy colonists, whilst they affected to despise the wild and untutored savage, felt a secret dread of him, and as for those who had come less in contact with him, the stories of the Red Indian's ruthless barbarity, blended as it was with traits of generous magnanimity, of his stoical indifference to physical suffering, and of his incredible sagacity in following up the trail of his enemies, seemed to invest him with a strange and almost supernatural power. Against such a foe mere bravery, or even the common prudence of ordinary warfare, was utterly insufficient, and the knowledge that there were a hundred red men in the ranks of the enemy entailed an amount of harassing precautions and fatigue that even the alliance of a thousand friendly Indians could do little to relieve. In the present struggle, which indeed may be said to have originated mainly in the jealous rivalry of Canada and New England to obtain monopolies of the trade with the red man, both parties were aided by many tribes of Indians. The powerful Iroquois, otherwise called the "Five Nations," with the Outagamis, the Fox Indians, and others, were for the most part allies of the English; whilst the Hurons, the Outamacs, the Morian Indians, and others, were generally found fighting on the French side.

The campaign of 1756 was opened with some inconsiderable advantages obtained by the French along the line of forts that lay between Montreal and Oswego. The erection of this latter fort, where the Onondaga river falls into Lake Ontario, had been amongst the first causes of serious enmity between the French Canadians and their New England neighbours, the latter having boldly planted this outpost right in the teeth of their rivals, for the better prosecution of their trade with the Indians—the great and ever-recurring subject of dispute. The reduction of this small stronghold was accordingly the first object of the Marquis de Montcalm, who this year took the command in Canada of the French forces, which had been largely increased by drafts from home. Fort Ontario, situated on the right bank of the river opposite to Oswego, was first attacked, and, running short of ammunition, owing to some unaccountable neglect on the part of the British, was carried in little more than twelve hours. The French artillery, and such guns as were found available in the captured fort, were then turned upon the more important stronghold of Oswego. The English commandant and many more of its brave defenders were soon killed, and on the 14th of August it fell into the hands of the French. It is to be lamented, however, that the massacre, by Montcalm's savage Indian auxiliaries, of a large number of the prisoners who had placed themselves under his protection, has cast a stain on the otherwise irreproachable character of the renowned and chivalrous commander, and tarnishes the glory of this brilliant exploit. The loss on the French side had been comparatively small, nevertheless the evening of that same 14th of August found the army surgeons busy enough, and from many a rude couch in the shed on which the wounded had been laid the doctor turned away with a shrug, which told plainly enough that all further human aid was hopeless. Such was the case with a certain Captain Lacroix, of the Regiment of Auvergne, who had at first seemed only slightly wounded; but symptoms of more serious injury suddenly became apparent, and one of his companions in arms, who now stood by his bedside, had just broken to him the intelligence that in a few hours more he would be no longer of this world.

"Yes," said the dying man, "I was afraid that it was so; and yet I hoped it might not be—for her sake, for her sake, Valricour. As for myself, what could I wish better than to die a soldier's death in the hour of victory? But my poor Marguerite! My heart bleeds for her, left so young without a father—without a friend."

"Say not so, old comrade," replied the other, scarcely able to speak for emotion. "I should be a base hound indeed if I could let such a thought embitter the last moments of an old brother officer to whom I once owed my life. Poor Marguerite shall never want a home—I swear it to you."

"I thank God! I thank God!" exclaimed the dying man, faintly, as he wrung the hand of his friend. But this effort, coupled with the sudden revulsion of feeling produced by the unexpected promise, proved too much for him, and poor Réné Lacroix fell back upon his pillow to rise no more.

For a brief space Valricour, and a young officer who had shared with him the task of watching by the bedside of his comrade, remained absorbed in mournful silence. It was at last broken by Valricour, who, half soliloquising, half speaking to his younger companion, sorrowfully uttered the words—

"Poor fellow! It was indeed a hard thing for him to leave her all alone and friendless here in a strange land. I could not but promise him that I would care for her, though how to set about it as matters stand is truly more than I exactly know at present. Well, we must see what can be done."

"His daughter is motherless too, is she not, my uncle?" said the young soldier.

"Yes, Isidore; she is, as he even now told us, utterly alone in the world, and penniless too, I fancy. When poor Lacroix came out with the regiment, and brought her with him, it was in the hope that he might ultimately obtain a grant of land here in New France and settle down upon it, for what little property he had was thrown away upon a worthless son, who died some little time ago."

Here M. de Valricour was interrupted by a summons to attend upon the general at head-quarters. He accordingly quitted the shed, leaving to young de Beaujardin the melancholy duty of seeing their friend consigned to his last resting-place amidst the battered outworks of the stronghold which his valour had helped to conquer.

When Baron de Valricour had spoken of his friend's having come to Canada in the hope of restoring his broken fortunes, he had, in some measure at least, described his own case. Though descended from an ancient family, he had never been a very wealthy man, and the lands of Valricour yielded an income quite inadequate to keep up a state befitting the chateau of so noble a house. The baron had made matters still worse by marrying, at an early age, an imperious beauty of like noble birth, but without a dowry, whose extravagance soon plunged her husband into difficulties, which gradually increased until there remained but one chance. By means of court influence he obtained a subordinate command in the army sent out to New France. A seigneurie on the St. Lawrence might well be looked forward to as the reward of military service when the war should be happily terminated; if not, it was something to be able to reduce the great establishment which otherwise must still be kept up in France. The Baroness de Valricour had yet another hope; the same day that witnessed her union with the young baron had seen his sister united to the Marquis de Beaujardin, one of the wealthiest nobles in the west of France. The Valricours had a daughter now in her twentieth year, whilst the Beaujardins might well be proud of their son Isidore, about a twelvemonth older than Clotilde de Valricour. The marriage of these two young people would blend into one the small estate of Valricour and the magnificent heritage of the Beaujardins. This was the cherished object of Madame de Valricour's life. Unfortunately for her design she had one day spoken of it to her husband, whose pride rebelled at the idea of purchasing an advantage for himself at the price of his daughter's hand. He had, moreover, no great liking for the young marquis, who carried to excess the luxury and affected politeness then so prevalent amongst the wealthy young nobles at the French court, where he was already a favourite. These were no recommendations in the eyes of his uncle, who had fought in the last wars, and had less of the polished courtier in him than of the bluff, straightforward soldier. But Madame de Valricour had no idea of being foiled by such small obstacles. Finding that her husband had resolved on going out to New France, she left no stone unturned until she had persuaded the Marquis de Beaujardin to obtain a commission for young Isidore, in order that he might accompany his uncle.

It may be observed by the way that Isidore was not obliged to enter the army as a mere subaltern, and to work his way up through the lower grades of command. As was usual with sons of the higher and more influential nobles, he became at once what was styled colonel en second, a second colonelcy being specially attached to every regiment for the immediate advancement of young soldiers of his rank and condition. Madame de Valricour not only hoped that by this proceeding she might keep the young marquis from the possibility of losing his heart at Paris, but she felt assured that she would overcome Monsieur de Valricour's dislike to him. With a woman's shrewdness she perceived that underneath those courtly airs and graces, and the silly affectation of extreme politeness which then prevailed in France, Isidore had many striking qualities which a little campaigning must needs bring out, and which would soon win the heart of M. de Valricour.

Thus it came about that Isidore de Beaujardin, instead of lounging amongst the gay and courtly throng in the brilliant salons of Versailles, found himself threading his way on the saddest of all errands amongst ghastly and disfigured corpses in the far distant wilds of Canada.

In one respect, at all events, the designs of the baroness were in a fair way to succeed; for her husband, though there was much in Isidore's habits and behaviour that irritated him at times, was unconsciously becoming daily more and more attached to his nephew. True, Isidore's hair was always dressed to perfection; his bow—that is to say, when he was off duty—might have gained a smile of approval at the king's levée or at one of the Pompadour's receptions; his hands would scarce have disgraced a lady; and the perfumes and cosmetics he used were as choice as they were multifarious. But then the same perfection was observable in his uniform and accoutrements, and the most exacting martinet would have sought in vain to find a fault in aught that pertained to his military duties. At the close of a long day's march under the burning sun that had knocked up many an old soldier, the young marquis seemed quite cool and ready for any fresh duty, whilst his imperturbable nonchalance, even when leading on his men to the assault, had called forth an exclamation of surprise from Montcalm himself, who was not slow to recognise true courage whenever he met with it.

So, after liberally rewarding the soldiers who had helped him in his sorrowful task, and with a sigh of commiseration for the desolate but unknown Marguerite, the young soldier betook himself to his quarters to attend to his toilet and get rid, as far as might be, of the distasteful and offensive traces of the day's fight. He had just completed that agreeable task, very much to his own satisfaction at all events, when the orderly who had previously called M. de Valricour away, once more made his appearance and informed Isidore that the Marquis de Montcalm desired his attendance at head-quarters.

otably short in stature and of slight figure, Montcalm had by nature an air and manner which at once powerfully impressed those who came across him, and the rapidity with which he habitually spoke tended rather to enhance the impression. He was endowed with a singular quickness of perception, an unusually retentive memory both for things and persons, and an unfailing judgment in the selection of the right man. These qualities, joined to an unvarying uprightness and a bravery of the most chivalrous character, not only won for him the esteem and affection of all who served under him, but stamped him unmistakably as one of those born to command.

When Isidore entered the shot-riddled building in which the marshal had taken up his quarters, he found him in conversation with Monsieur de Valricour. The young soldier accordingly saluted, and then remained standing near the door, whilst Montcalm, dropping his voice so as not to be overheard, concluded as follows:—

"As for me, I do not think so badly of these dandies as you do; some of them only need to have all the pains they take upon themselves directed into the proper channel to realise great things. From what I have seen of our young friend I think he is one of these; at any rate I will give him the chance." Then, turning to Isidore, he added aloud: "Monsieur de Beaujardin, I have noticed with satisfaction your courage and self-command during the assault, and have selected you for a duty of importance. You will take this despatch and deliver it, with the least possible delay, into the hands of Monsieur de Longueuil at Fort Chambly. On your way you will observe the formation of the ground and any obstacles or facilities for the march of troops, and will take note of any appearance of an intention on the part of the enemy to throw forward advanced posts on your line of route. At Chambly you will hold yourself at M. de Longueuil's orders either to return or proceed elsewhere."

Isidore took the despatch which the general held out to him, and as the latter remained silent, he again saluted, and was turning to withdraw when Montcalm stopped him, saying—

"You seem to make very light of the matter, my young friend; but you will not find the task before you so easy an affair as dancing a gavotte or a minuet, I can tell you. Do you know that Chambly is some seventy leagues distant? How do you mean to find your way there?"

"I presume I shall be furnished with a guide, and if so, I shall trust to him for that; if not, I shall find the way as best I can."

"Yes, and get scalped by some of our red friends before you have gone a league; and then what becomes of my despatch on the king's service?"

"In that case," replied Isidore, coolly, "I shall be no longer in His Majesty's service, and be accountable to another King for having at least done my duty."

"Good," said Montcalm. "You will find that I have provided you with a guide—one in whom you may place implicit confidence. Adieu, sir."

On leaving the general's quarters Isidore was followed by Monsieur de Valricour.

"I congratulate you heartily, my dear fellow," said the baron. "Our general has evidently taken a fancy to you; only carry out this affair to his satisfaction, and the path to distinction is open to you. As for me, I am under orders to convoy the prisoners to Quebec. I am glad of it, for, in the first place, the slight wound I have received——"

"You wounded, my uncle?" exclaimed Isidore anxiously. "I hope it is really slight; you are apt to think too lightly of such a thing."

"Oh, it is only a trifle, and there will be no great fatigue on the march, as we shall probably go by water if we can find boats enough. At Quebec I can rest and take care of myself; besides, I shall thus be enabled to break the sad tidings myself to poor Marguerite, who is staying there, and take measures for sending her over to France. Aha! here is your guide; you will find him a first-rate fellow, and as true as steel. Moreover, I fancy there are not many men, red-skinned or white, who know the country you have to traverse better than our friend Jean Baptiste Boulanger, woodman, voyageur, trader in peltries, and everything else that can make a man at home in the backwoods."

Isidore looked at his guide, whose countenance seemed, to confirm this favourable opinion. The Canadian looked at him, though more covertly, and it must be owned that his face did not betray any evidence of a similar good opinion of the young marquis. On the contrary, it was in a rather sulky tone that, after touching his cap, the guide observed—

"Monsieur does not intend to make the journey in his uniform, and in those boots?" (The last words were especially emphasised.) "If I might be so bold, I would suggest a peasant's coat like mine, and a pair of moccasins as likely to——"

"I go as I am, Master Guide," replied Isidore curtly. "Mind your own business."

"H'm—well, perhaps you are right," said Monsieur de Valricour. "Yes, stick to the uniform; a soldier cannot well do wrong in that, when there is any doubt."

"Monsieur at least will take with him some better weapon than that small sword," urged the Canadian. "But perhaps monsieur is not used to carry a musket?"

"Yes, yes, do so, Isidore," said the baron. "Do that by all means; one doesn't know what one may come across on such a journey."

Isidore would probably have refused, but that he felt somewhat nettled at the guide's last remark, so he took a rifle from a pile of arms that stood close by. To this the baron would fain have added a knapsack, and Isidore seemed by no means disinclined to take one, as it would enable him to carry with him some articles pertaining to the toilet, which to him were rather necessaries of life than mere comforts or luxuries. Here, however, the guide again relentlessly interfered, declaring it to be worse than useless. "A light load makes a quick journey," said he; "monsieur would be glad enough to get rid of it before the end of the first day's march. My game-bag will suffice for both, and I have taken care to stock it with all that monsieur can want on such a journey." Isidore gave way, perhaps not very graciously, but a glance at the figure and equipments of Boulanger made him feel that he was in the presence of an unquestionable authority in such matters. He had indeed some slight misgivings that he had been rather hasty in the affair of the boots, and that he was likely enough ere long to envy the guide his light and roomy moccasins, to say nothing of his loose leggings and the well-worn frock of grey homespun that had evidently seen service in the woods. Even the gay wampum belt spoke of an ease and comfort to which the young French soldier's stiff sword-belt could not pretend. In fact Jean Baptiste Boulanger, or "J'n B'tiste" as he was familiarly called, with his leathern game-bag slung over one shoulder, his long rifle over the other, and his Indian knife, with its gaudy sheath, hanging at his side was the very beau-ideal of a Canadian forester of those days, and if his features did not just then give evidence of his natural bonhomie and kindliness of heart there was that in his sunburnt face and keen dark eyes that inspired confidence at the first glance.

These important preliminaries were scarcely settled when a hue-and-cry was heard, and no little commotion arose. It turned out that an Indian had been found huddled up, apparently asleep, in a corner of the room adjoining the one occupied by the Marquis de Montcalm himself. He proved to be not one of those acting with the French troops, but an Iroquois, and on being detected had darted through the open window, and though the alarm was instantly raised, had succeeded in baffling his pursuers and making his escape. Such incidents, however, were not so uncommon as to excite more than a passing notice, and as soon as the outcry had subsided the baron took an affectionate leave of the young envoy, who, accompanied by his guide, forthwith set out upon his journey.

The circumstances under which the travellers had commenced their acquaintance were not calculated to produce very quickly a good understanding between them. The woodsman, rough as he was, had a sensitive disposition, which chafed under the rebuff with which his well-meant advice had been met. After crossing the river and leaving Fort Ontario behind them, they plunged into the apparently trackless forest, and for some time neither of them spoke a word. Boulanger strode on, eyeing his companion askance, and possibly speculating whether the fine gentleman who had treated him so superciliously would not very soon be forced to give in, and perhaps commit to him the task of proceeding alone to their intended destination. Isidore seemed indeed scarcely the man for a task like that which lay before them. Rather under the middle height and slightly built, he had apparently been little accustomed to severe or protracted exertion, whilst everything about him bespoke the petit maître, if not the fop. In the meanwhile the young marquis had not given a second thought to the few words that had passed at the outset of the journey. Being habitually reserved towards his inferiors, he was content to indulge in his own meditations without caring what such a man as Jean Baptiste Boulanger might think about him. The guide, however, had no notion of being kept at arm's length by a man with whom he was to traverse those lonely woods for the next week; and as he observed the coolness, and still more the agility, with which Isidore met and surmounted some little difficulties that soon presented themselves on the way, he began to warm towards him and to feel half sorry that he should have been put to an undertaking that might prove too much for him. It was probably some feeling of this kind that at last brought out the words—

"And how far does monsieur mean to march to-night?"

"Nay, my friend," replied Isidore, "that is for you to arrange; I never interfere with the business of other people. You are the guide; you know the distance and the road. It is for you to settle the length of the stages, and where we are to encamp for the night, as I suppose, from the little I know of these parts, that we have not much chance of sleeping under a roof between this and Fort Chambly."

"Bravely spoken, monsieur!" exclaimed Boulanger, thoroughly restored to good-humour by these words. "Monsieur will pardon me for having had my misgivings as to the length of the marches that might be accomplished by—by a personage like yourself, not used to this kind of work. Well, then, I propose that we halt at midnight; that will be enough for a start, and it will bring us to good camping ground. I think we had better do the greater part of our work by night, and rest and sleep during the heat of the day. We shall do more, besides escaping notice in case there should be any scouts, either white or red, or marauding parties prowling about, as is sometimes the case near the border."

"I should have thought there was small chance of meeting any one in these interminable woods, through which, as a matter of taste, I should prefer to travel by daylight," replied Isidore. "Indeed, I am rather thankful for the bright moonlight we seem likely to have, and wish we had a few more of such open glades as the one we have just crossed; it would be more agreeable—at least to me."

They had re-entered the wood, and had not proceeded very far when they came to a spot that would have been particularly dark owing to the great size of the trees and their closeness to each other, but for the few gleams of moonlight that found their way even through the dense foliage and lighted up a branch here and there with a strange and almost supernatural brightness. Suddenly the guide stopped, and slightly raising his hand as if to keep back his companion, gazed intently for a moment at a good-sized button-wood tree that stood at a distance of about thirty yards, but somewhat out of their course. Following the direction of the Canadian's eyes, Isidore looked wonderingly at the tree, when suddenly he saw a dark shapeless object drop from one of the lower branches. He expected of course to see it lying on the ground beneath the tree, but not a trace of it was visible; it seemed as if the earth had swallowed up the big dark thing, whatever it might have been.

The guide, who had half raised his rifle, now lowered it again. "The rascal has got off this time," said he, "but who would have expected to come across a red skin hereabouts just now? Stop a bit! Depend upon it, this is the same fellow who was found skulking about the general's head-quarters this evening. Yes, he is dogging our steps, and we shall hear more of him before we get to Chambly."

There was something about this announcement that was not at all pleasant to Boulanger's companion. He might be brave as a lion and cool enough in fair open fight, but the idea of being the object of a planned attack by Indian savages in the depths of a lonely American forest somewhat disconcerted him, and he looked rather anxiously around, as if each tree might harbour another lurking enemy.

"Nay, monsieur!" exclaimed Boulanger, "we shall not be troubled by any more of them just yet. There is not much hereabouts to tempt the red skins to come this way. That fellow was but a single scout, and he won't attack two men armed as we are; having made sure of our destination and the route we have chosen he is off by this time to join his friends, who may very likely make a dash at us two or three days hence; but Jean Baptiste is too old a hand to run into a trap with his eyes open. We will give them the slip yet by changing our route a little. We shall have to pass a small New England settlement, but——"

"An English settlement!" exclaimed Isidore, "that would surely be running into a trap, as you call it, with a vengeance."

"Not a bit," replied Boulanger; "I have been through fifty times as voyageur, trader, or what you will, and one of the settlers, John Pritchard, married a sister of mine, and the settlement is too near the border for them to do an ill-turn to a Canadian; still, with that uniform, it may be best for you to keep close and not show yourself, whilst I visit my old friends and lay in what is needful. We shall be safe enough. Allons!" So on they went.

Isidore could not fail to be struck by the unhesitating certainty with which his companion threaded the intricacies of the apparently interminable forest, through which he could detect no path or track of any kind, much less anything in the remotest degree resembling a road. There were, indeed, such things as tracks in the woods, though perhaps a league apart, but the practised eye of the Canadian forester needed none; his habits of observing every peculiarity, whether on the ground or above, enabled him to keep not only a direct course, but one which avoided any obstructions or impediments to their progress. Boulanger said that he had been used to these woods ever since he was born, some forty years since, and had lived in those parts until two or three years previously, when he had removed to the neighbourhood of Quebec with his wife, whom he called Bibi. His experience in all things pertaining to the woods had obtained for him a situation under the manager of the Royal Chase, as it was called, but he had been engaged by Montcalm, who had the gift of selecting the best man for every business, to act as one of the guides to the troops in the present campaign. After conducting Isidore to Chambly he was to have his discharge, and would be at liberty to return home; but it was plain that the last few months had revived in him a love for his old independent way of life, which doubtless contrasted strongly with his new position. It galled him to work for wages, however high, however certain, and his servitude brought him into contact with much at which his disposition revolted. So, as he told his story, he gradually grew more and more excited, declaiming hotly against the evils he had seen and heard of since he had quitted his log hut in the forest. For some little time Isidore listened with patience, or rather indifference, to his guide's indignant invectives against the various misdoings and iniquities of the creatures and underlings of the Government, and especially of those employed by Bigot, the king's intendant. At last, however, in his excitement, Boulanger began to launch out against Monsieur Bigot himself, whereupon he was somewhat sternly called to order by his aristocratic young companion, who bade him remember that it was not for such low-born fellows as he to open their mouths against the seigneurs and nobles, and least of all against the officers of His Most Christian Majesty. Had the guide been a New England colonist, rejoicing in the name of John Smith, he would probably have retorted boldly enough and held his ground, but what could be expected from Jean Baptiste the Canadian woodsman? He might have sense enough to understand the wrong-doing, and in the honest zeal of the moment he might inveigh against it, but it was not for him to set himself up against monseigneur the young Marquis de Beaujardin. There was a murmured apology, mingled with some kind of protest that it was all true, nevertheless, and then our travellers continued their journey for a while in the same unsatisfactory silence with which they had commenced it.

This state of things, however, did not continue very long. The young marquis, though he had considered it incumbent on him to rebuke a person who ventured to speak in such a way of the nobility, was not one to persist in assailing an adversary who had succumbed to him. Moreover, even his short experience of affairs in Canada told him that Boulanger had good grounds for what he said. The courtly magnificence of Versailles and the Tuileries might dazzle his understanding so far as to blind him to the existence of many crying evils in old France, but here there was nothing to gild and gloss over the corruption and mismanagement that everywhere prevailed. The shameful monopoly of all commerce by the Merchant Company; the iniquitous sale of spirits by the Government to the Indians; the rapacity exhibited in the system of trade-licences and other extortions by which the officials wrung from the humbler classes whatever could be got by fair means or by foul; to say nothing of the scandalous effrontery with which the Government itself was robbed by its own officers in every conceivable way—all these stood out in their naked deformity, and had more than once made Isidore wonder how a people thus treated could remain so generally loyal as the Canadians undoubtedly were. He was, consequently, ready enough to give his guide credit for honesty in his indignation, whilst the courtier-like habits he had already acquired in the salons of Paris made him appreciate the desirableness of being on fair terms with one who held not only his comfort, but probably his life, in his hands. He accordingly took the first opportunity of dropping some remark expressive of the admiration which he really felt for the beauty and grandeur of the forest through which they were just then passing.

He had touched a chord in Boulanger's breast which was always ready to vibrate.

"Yes, monsieur," exclaimed the latter, forgetting in an instant the rebuff he had recently received; "yes, here, indeed, all is peaceful and happy, for all is as it comes to us from God's hand. The folly and wickedness of man have not yet invaded these sublime yet lovely solitudes. All things around can but remind us of the days when the world came forth from the hands of our Father, and He said it was very good. Come, monsieur, it is time we should call a halt, and take some supper; we have done very well, and made a good beginning. Let us sit down here under this noble tree, and rest and refresh ourselves."

Thereupon the travellers seated themselves, and Boulanger produced from his game-bag a plentiful supply of provisions, which soon disappeared under the keen appetites resulting from the night's march, following on a day of hard work and light rations.

o further incident worth notice occurred either during the remainder of the night or on the two following days. Thanks to Boulanger's experience and to the genial August weather, Isidore found none of the inconveniences he had anticipated in this impromptu journey, and slept perhaps more soundly than he had ever done before during the long halts which they made in the heat of the day. On the third day, late in the afternoon, they approached the English settlement of which Boulanger had spoken.

They had reached the top of a small ridge that looked upon the clearings, the guide being perhaps a dozen yards in advance, when, just as Isidore came up to him, the Canadian turned, and grasping his arm, exclaimed, "The Indians! the Indians! Look! the Indians have been there and destroyed the place. Alas! would that this were all. I fear we may hardly hope to find one soul alive."

A single glance at the scene before them was sufficient to satisfy Isidore that his companion's supposition was only too well founded. On the extensive clearings spread out in the valley below he could plainly see the remains of the half dozen homesteads, now either mere heaps of ruins, or at best with only some portion left standing, like blackened monuments serving to mark the spots where the bright hopes and joys of the once happy little community, nay, perhaps they themselves, lay buried for ever.

"Let us go down," said Boulanger, as soon as he recovered from the first shock, "let us go down; it is not so very long since this has happened, surely they cannot all have perished—at least we may learn something as to how this came about, and if any yet survive." They descended the hill, and scarcely had the guide begun to cross the first tract of cultivated ground when the mournful expression of his face changed to one of curiosity and surprise.

"Why, what is this?" exclaimed he, pointing to a dark object that lay at a short distance from the spot. "A dead Huron, and in his war paint! Yes—and there lies another. There has been a fight here not many hours since, and the red skins have been worsted or we should not see that sight, and yet the half dozen men belonging to the place could have been no match for them." Boulanger hurried forward, Isidore following him, and they soon came to an open spot that had served as a kind of village green, on which many articles of various kinds were strewed about. "Look here, and here!" cried he, now seizing Isidore by the arm and pointing first in one direction, then in another. Half irritated at this familiarity, half bewildered by Boulanger's words, Isidore gazed about him; but the broken musket, the extinguished camp-fire, the rudely tied up bundle of spoils, such as none but a Red Indian would prize, were to him wholly without meaning. To add to his perplexity, Boulanger, who had been scrutinising everything around them with eager curiosity, suddenly quitted his side, and vaulting over a fence, disappeared in the wood that skirted the clearing.

"Hang the fellow!" muttered Isidore. "This is a little too bad. If he expects me to follow him everywhere, he is mistaken. A pretty thing, truly, if I were to miss him and lose myself in this out-of-the-way place, I'll let him know that it is his business to attend to me instead of running about to look after dead savages, or live Englishmen either."

The guide, however, soon reappeared, saying, as he rejoined his companion, "There are red skins enough lying in the wood yonder. They must have been surprised here after a successful attack on some other place, and the people here have had little or no share in it, but have been helped by some much stronger force than they could muster. That's plain enough, at all events."

"It may be all plain enough to you," replied Isidore. "As for me, I can see there has been a fight between the white men and savages; but more than that I cannot make out, and in truth I don't see that it matters much to us, except that we are disappointed of our expected quarters for the night."

There was a look of anger not wholly unmixed with contempt on the face of the Canadian as Isidore concluded these remarks.

"Truly," said he, "I had forgotten, in my anxiety for the fate of many who were no strangers to me, that monsieur may lose his supper and his bed."

The rebuke was not thrown away. Beneath all his aristocratic pride, and the selfishness that had grown upon him, Isidore still had a heart capable of sympathy and compassion, and there was a nobleness in his nature which at once compelled him to avow his error even to so humble a companion.

"Forgive me, my friend," said he; "I have deserved your reproof. Come, let us at least see before we go further whether we can find in any of these ruined buildings something that may give us a clue to what has befallen your friends. As it is clear that the Englishmen had the best of it, perhaps we may find that the people of this place have only gone elsewhere for temporary shelter."

Boulanger was appeased in a moment; his was one of those rare dispositions with which a little kindness outweighs more than a like amount of harshness and injustice.

"Enough! enough! monsieur," said he. "That is a good old French proverb which says, 'A fault avowed is half pardoned,' though I think that 'wholly pardoned' would be better still. Let us do as you propose; afterwards we will continue our journey for a short league, so as to get away from this miserable scene, and then we will encamp for the night."

Keeping purposely away from that part of the settlement which had been the scene of the terrible tragedy, they crossed two or three of the clearings without coming upon anything worthy of notice, except that the buildings, and in many places the growing crops, had been wantonly destroyed. At length they reached the homestead which had belonged to Pritchard, Boulanger's relative. It was about half a mile from the spot where they had first come upon the settlement, and, perhaps owing to its somewhat remote position, had escaped better than the others, one-half of the house being almost uninjured. With a deep sigh Boulanger pushed open the door, but immediately started back as a man, who had been sitting there with his face buried in his hands, rose up hastily and surveyed the intruders with surprise evidently not unmingled with fear. He was soon reassured on perceiving that one of his unexpected visitors was Boulanger, who on his part was not slow to recognise his brother-in-law.

They soon learned from him that things had come to pass pretty much as Boulanger had surmised. A formidable body of Indians, numbering full a hundred warriors, had about a week previously crossed the St. Lawrence and made an incursion into the New England territory. Fortunately the settlers at Little Creek had been warned of their danger by a half-witted Indian orphan girl, on whom Pritchard had taken compassion some time before, and who had become domesticated amongst them. They fled in haste, leaving everything behind them, and the Indians having other objects in view did not turn aside to follow them; but after ravaging the place hurried on to attack a yet larger settlement, further from the border, whose inhabitants had thought themselves far removed from any such inroad. The onslaught was as successful as it was sudden. The men were for the most part absent; the settlement was sacked, the women and children were either killed or carried off as prisoners, after which the Indians turned back, and having again reached Little Creek encamped there and gave themselves up for the day to celebrate their victory with their usual savage rites, and to indulge their greedy thirst for the fatal fire-water of their enemies. But the New Englanders had not been idly weeping over their misfortunes. Hastily collecting every man who could bear a musket, they followed up their retiring foes and came upon them in the midst of their drunken carouse. Burning with the desire of revenge, and infuriated by their recent bereavement of all they held most dear, they fell upon the almost unresisting Indians and massacred them to the last man. Then they in their turn retreated to rebuild their ruined homesteads and mourn over the dead. Some stragglers of the party had told all this to the fugitives from Little Creek, and Pritchard had ventured back to the place to make sure and report to the rest whether the coast was really clear for them to come back again. Such was the border warfare of those days.

The travellers now abandoned their intention of going further that night, as Pritchard urgently pressed them not to leave him there alone, and Isidore indeed was hardly in a condition to continue the journey. The house had not been plundered, so Pritchard was able to offer them what they needed in the way both of rest and refreshment. When their frugal meal was over it was arranged that each of them should keep watch in turn. There was indeed no likelihood that any one would come near the spot, or that they would be molested in any way, nevertheless there was something in the awful solitude of the place that seemed to create a feeling of insecurity. The first watch fell to Pritchard's lot, and Boulanger took the second. Isidore thought he had only just dozed off when the guide awoke him, and told him that it was his turn.

"Why, it is still daylight," said he, rubbing his eyes, "unless indeed—— You do not mean to say it is morning?" he added, half vexed, as the thought arose in his mind that the Canadian had compassionately allowed him to sleep on beyond this time.

"Monsieur is less used to the forest than we are," replied Boulanger, good-humouredly. "I had one spell of sleep to begin with, and another hour's rest will set me up for a week to come." So saying he stopped all further discussion by stretching himself on the floor, and apparently dropping off at once.

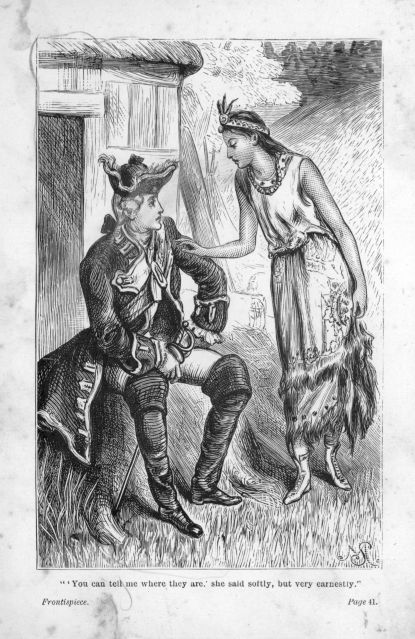

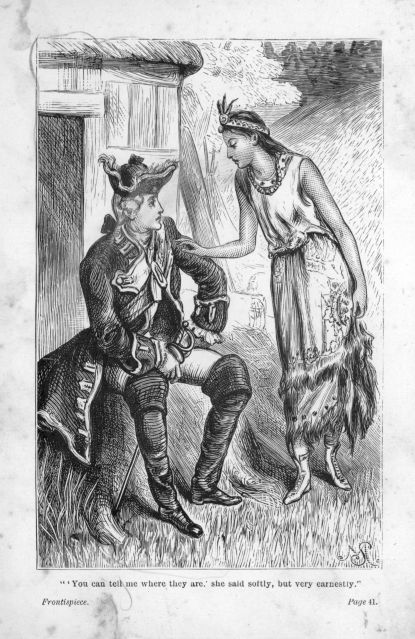

Isidore rose and went out; then, seating himself on a great stump that stood near the door, he gazed out upon the still and desolate landscape, which was just distinguishable in the first grey light of morning. He had become absorbed in a reverie on the events that had brought him into so strange a locality when he felt his arm lightly touched, and, looking round, beheld, to his great astonishment, a young Indian girl standing by his side. His first impulse was to start up and give the alarm to his companions; then came a feeling of shame at such an idea as he scanned the girl's face, from which one might have supposed her to be twelve or thirteen years old at most, although, judging from her stature and figure, she was probably some years older. There was, however, a strangely forlorn expression on her features that went to Isidore's heart as he looked at her. Perhaps she noticed the impression she had made upon him, for she again laid her hand upon his arm, saying, timidly, "The pale faces are very wise. Can the young warrior tell Amoahmeh where they are?"

This was much too mysterious for Isidore; in fact, it suggested to him at once all sorts of Indian wiles and stratagems. What if there was a whole tribe of red men in the next cover! Without more ado he called to Boulanger and Pritchard, who instantly came rushing out of the building rifle in hand.

"Hola! what have we here?" exclaimed Boulanger, looking round as if the Indian girl had suggested to him the same possibility of an Indian attack as had occurred to Isidore.

"Oh, 'tis only Amoahmeh," said Pritchard, quietly, as he recognised the cause of their alarm. "It is all right; she is the half-witted Indian girl—if she has any wits at all—of whom I was telling you. I fancy some of the red skins with whom her tribe were at war butchered all her family in bygone days, and she is always bothering one to tell her where they are—I suppose she means her kith and kin. I always tell her that it is of no use asking what has become of a lot of heathens like them."

"But," said Isidore, rather interested in the poor girl, "how was it she escaped when all her friends were killed?"

"Well," replied Pritchard; "perhaps she became crazy then, and was spared on that account. The red skins are queer folk, and never harm crazy people. For that matter, they might teach a lesson to some that call themselves Christians. They seem to think idiots something supernatural, and call them 'Great Medicine.'"

"Yes, that's true enough," said Boulanger; "I suppose the child has had wit enough to keep out of the way of those New Englanders, and has been hiding about in the woods during all this business. Well, if that is all, we may as well turn in again. Monsieur need have no fears," added he, addressing Isidore; "the best way is to take no notice of her. At all events, if she does skulk about, she is more likely to warn us of any danger than to bring it upon us." With these words the guide, followed by Pritchard, again entered the house, leaving Isidore alone with Amoahmeh.

During this little interlude the girl had eagerly watched each speaker in turn, apparently trying to follow what was said. It was but too evident, however, that all was a blank to her except an occasional word, at which her face would once and again lighten up with intelligence. Isidore could not help being touched by her desolate condition, and when Pritchard and the guide had left them, he turned towards her to bestow on her a few kindly words, but Amoahmeh had timidly retreated to a little distance and had seated herself at the foot of a tree, apparently absorbed in conning over what had passed.

Let us be as tender-hearted and compassionate as we may, a pain in our little finger must still come home to us more than another's loss of a limb, at least, if there is no special link between us. Isidore's pity for the half-witted girl was presently lost sight of in what had first been only the inconvenience, but had latterly become the positive suffering inflicted on him by those unfortunate boots of his. Pride alone had restrained him from hinting at this to Boulanger during the latter part of the day's march; but he now began to have some misgivings as to whether he might not become wholly incapacitated from proceeding further unless he put his pride in his pocket and adopted the suggestions of his guide. Here was, however, a chance of temporary relief at least, as he was likely to be unmolested for a couple of hours, so he proceeded at once to divest himself of the said boots, a business that was not effected without much pain and exertion, and an unmistakable aggravation of the mischief. He was just debating with himself on the advisability of bathing his swollen ankles in a tempting stream that rippled along only a few yards off, when he was surprised to find Amoahmeh—who had been watching his proceedings with an interest of which he was wholly unconscious—kneeling before him, evidently intent on applying to the inflamed and aching joints a quantity of large green leaves which she had just gathered for the purpose.

There are probably few amongst us who have not, at one time or another, experienced that ineffably exquisite sensation caused by the sudden cessation of intense and wearing pain. For a minute or two Isidore could, only look down complacently on his ministering angel, giving forth more than one deep and long drawn sigh of relief; then naturally enough pity for her once more awoke within him, and he exclaimed, "Poor child! now this is very thoughtful of you. Really one must admit that there are some things in which even a mere savage has the advantage of us. Yes," he added thoughtfully, "I wish I could do something to lighten your troubles and hardships."

The girl looked up in his face. His words had fallen dead, but the tone in which they were spoken reached her heart.

"You can tell me where they are," she said softly, but very earnestly.

"Where they are," repeated Isidore. "Ah, well. Do you mean your father or your kindred?"

"Tsawanhonhi is in the happy hunting grounds—Amoahmeh knows that," answered the girl, quietly yet firmly. "Yes, and Wacontah is with him—I know that too. But—but the little ones, Tanondah and Tsarahes, my brothers—where are they? Oh! who will tell me where they are?"

Isidore was silent. "I suppose," thought he, "these must be the little ones that she has loved and lost; Pritchard said something of her friends having been all killed."

He looked at her sorrowfully, for the eager, inquiring face troubled him, he scarce knew why.

"The pale faces know what the Great Spirit says about all things. Will the young brave hide this from poor Amoahmeh?" said she with a yet more wistful look.

"Now what is this fellow Pritchard," said Isidore to himself, "or what am I, ay, or what is even Monseigneur the Archbishop for that matter, that we should take upon ourselves to say what a loving Father in His wisdom may choose to do with these red skins after they leave this world?"

"My good girl," he blurted out, after a short pause, "the Great Spirit has taken your little brothers, and keeps them safe enough in a place that He has made on purpose for them. The Great Spirit is a good Spirit, and you may be quite sure that He would not hurt your little brothers. You have found trouble and sorrow enough already in this world to enable you to believe that the poor little fellows may be all the better for being taken out of it."

"Ah, yes!" replied Amoahmeh, looking gratefully up in the young soldier's face, "I was sure the pale face knew where they were. But," she added earnestly, "can he tell me whether I shall see them again?"

"See them again!" rejoined Isidore, apparently somewhat puzzled for the moment. "Ah, well, I don't know why you should not. I think," he muttered, "I may go as far as that, though she is but a heathen. At all events it will be some comfort to the poor thing."

It did comfort her indeed. Perhaps she only understood it very partially, but the one absorbing uncertainty that had troubled her was cleared away. She took Isidore's hand and kissed it; no tears fell upon it—perhaps it would have been well with her could she have wept. Then she arose, and before he could call to her, she had disappeared.

With a pleasant sense of relief from bodily suffering, and with a mind not particularly pre-occupied by any anxiety, Isidore passed the remainder of his watch in recollections now of the courtly assemblages at Versailles, now of the voyage out to New France, now of the assault at Oswego, as the current of his ideas was swept hither and thither by some casual link of association, and he was only aroused from his meditations by the appearance of the guide, who came to warn him that breakfast was ready within, and that they would have to start in a quarter of an hour so as to make good way daring the cool of the morning.

As Boulanger said this his eyes lighted on the green bandages that still enveloped Isidore's ankles. The facts were of course soon told, and Boulanger was loud in his praises of the girl's thoughtfulness, though he did not disguise his fears that the resumption of the boots and a day's march in them would be a serious matter. At this juncture Amoahmeh once more made her appearance, bringing with her a pair of Indian moccasins, with leggings to match, on the manufacture of which out of materials found in one of the deserted dwellings she had been busily employed since her interview with the young soldier. Great was Boulanger's delight, while Isidore on donning the new made, and by no means unornamental moccasins, declared that nothing could be more comfortable, and that he felt able to accomplish any journey that the guide might think fit to lay out for the day. He would have expressed his thanks to the girl, and indeed he would have made her a handsome present, and bestowed on her a kind word at parting, but she was nowhere to be seen. The morning meal did not occupy much time, and after taking leave of Pritchard, Isidore and the guide set out on their day's march.

n quitting the clearings, Isidore and his guide once more plunged into the seemingly interminable forest, and had proceeded about half a league when Boulanger, whose eye appeared to be unceasingly on the look-out, cast a glance behind him and then came to a halt, saying, "Why, there is that girl again! What can she be up to?"

Isidore looked round, and there she was, sure enough. Amoahmeh, too, had stopped and remained standing about a hundred yards from them, but she showed no signs of wishing to avoid notice, and looked as if she only waited for them to go on in order to follow them.

"This will not do," exclaimed the guide; "she must have some object in tracking us like this. Hola! come here," he added, beckoning to her. Amoahmeh was at their side in a moment.

"What do you want? where are you going?" inquired Boulanger, sharply.

The girl looked timidly at him, then gazed for a minute in Isidore's face.

"The young brave knows where they are," said she; "I am going with him."

"With him! Nonsense," ejaculated the Canadian, "you can't go with him. Get you back, there's a good girl. Pritchard and the rest of them will be at the old place before nightfall, I daresay. You must go back to them."

The girl did not answer, neither did she manifest any disposition to do as Boulanger desired her.

"Peste!" said the latter. "One doesn't know how to deal with these idiots; it's of no use talking sensibly to them, and they are as obstinate as mules. Monsieur must try to make her go back. One cannot beat her, you know," he added half apologetically, as the thought of Amoahmeh's resolutely refusing to relieve them of her company probably suggested some such extreme proceeding.

"Beat her!" exclaimed Isidore indignantly, "I should think not. My good girl, I cannot take you with me. You must go back to your friends."

She looked at him long and wistfully. At last she said, "You are my friend, you know where they are. I will go with you until we find them."

Boulanger struck the end of his rifle on the ground despair. Isidore was puzzled, but suddenly a thought struck him.

"If Amoahmeh goes with me," said he quietly, "I shall be discovered by the English, and if they find me they will shoot me."

She looked inquiringly at him as if she half understood the purport of his words.

"To be sure," interposed the guide. "Do you want him to be shot? If not, you must go back." There was a short pause; then Amoahmeh bowed her head, and crossing her hands over her bosom turned away and began to retrace her steps towards the settlement.

The young soldier made a gesture as though he would have recalled her, but Boulanger stopped him. "Let her alone, monsieur, for goodness sake. But for that lucky shot of yours we should never have got rid of her; and think, only think, monsieur, the further she had gone the more impossible it would have been for you to shake her off. Do you want her to stick to you all your life?"

Isidore admitted that the guide was right, and on they went. Yet his heart was full of pity for the poor child as he looked back and saw her stealing silently away through the wood, and he felt that he had been compelled to extinguish the ray of sunlight that had shone in upon the darkness of her soul.

The travellers halted before noon and rested for some hours. They then pursued their march until near sunset, when they came to the elevated ridges which divide the small rivers flowing northward into the St. Lawrence, from those which run southward towards the West Hudson and the Ohio. Boulanger's object was to reach a village situated amongst the numerous small lakes in this district, and obtain a canoe, by means of which he might greatly lighten the rest of their journey. The Indians were of a friendly tribe and knew him of old, so he had no fears about the reception they might give him.

"In ten minutes," said he, "we shall reach the largest lake about here, and at this season we can skirt along its banks instead of having to go over yonder hill—no light task after the close of such a march as we have had to-day." As he spoke, a form was seen bounding towards them with the swiftness of a young roe; both stopped amazed, as Amoahmeh sprang forward, and laying her hand on Boulanger's arm, pointed with the other towards the leaf-covered ground, and uttered the single word "Iroquois."

Isidore of course saw nothing, but the practised eye of the Canadian was not slow, now that his attention had been roused, to detect the trail of footsteps that had crossed their track. "The girl is right," said he, after a rapid but close inspection of them, "and take my word for it, it is the trail of our old friend of the button-tree. Yes, he has been tracking us all the way. Now, look at that! The child came upon it this morning, and has followed it; she has caught him up, and has come to warn us of——"

Here Amoahmeh placed her finger on her lips, and made a gesture of impatience.

"Right, child," said Boulanger. "To think now that a bit of a girl like this should have to teach me to keep my tongue from wagging too loud."

"But what are we to do?" asked Isidore, somewhat bewildered by all this.

"Do!" repeated the guide. "Well, we had better leave that to her. Questions would only puzzle her poor brain, whereas it is clear she has still got all the red skin's cunning, and won't let any harm befall you at any rate."

Probably Amoahmeh understood the expression of his face better than his words. At all events she took upon herself at once the office of guide, and beckoning to them to follow her turned off from the direction they had been taking and led them into the wood. In a few minutes they found themselves on the borders of a creek, scarcely a dozen yards from the point where it ran into a lake of great extent, and there, to their surprise, Amoahmeh pointed out two or three canoes which had evidently been purposely drawn up under some overhanging bushes, so as to escape the possibility of being observed either from the forest or the lake.

By this time a perfect understanding had been established between Boulanger and their new guide, and they seemed to need a few signs only to express their meaning. A good many whispers, however, were necessary in order to make Isidore crouch down in the middle of the largest canoe without upsetting the frail craft, but as soon as he had done so his companions stepped lightly in, one at each end, and the next moment they were silently paddling out into the lake.

Again Boulanger made a sign; stealthily they paddled back, and the Canadian reached over into the other canoes in succession, and with a few strokes of his Indian knife ripped them up after a fashion that did away with all chance of pursuit from that quarter; this done, they once more regained the lake.

After pausing for a few seconds to listen, Boulanger and the girl, as if with one consent, drove the canoe close under the bushes that fringed the bank and here and there hung down and dipped their long branches in the water. Isidore's impatience and curiosity now became so great, and his sense of his own rather undignified position so galling, that he was just about to assert some kind of right to know what and whereabouts the danger might be, when he was stopped by the sound of voices upon the bank at no great distance from them. A few more strokes of the stealthy paddles and the voices were distinctly within hearing.

"And I say," exclaimed some one in English, "that I am not going to stay out here all night on such a wild-goose chase."

"Nor I," said another. "You, Master Kirby, may stop here with them that will; some of us have sorrow and trouble enough at our own doors that call us home instead of loitering here. Besides, who knows that the whole thing isn't a lie of this red scoundrel's after all?"

"You placed yourself under my orders, and I bid you stop here," replied a firm voice. "The Indian's story was clear enough as he told it at first, before you were such fools as to let him get dead drunk after his hard run. What more likely than that Oswego has been taken by that rascally Montcalm, or that he should send important despatches across country this way? I know this Indian fellow well: he is trustworthy enough when sober, and he says he not only saw the French officer and his guide start from Oswego after the disaster there, but left them not two hours ago on a path that must bring them either along here or take them over the hill, in which latter case they will fall into Tyler's hands."

As these various views and opinions were uttered the canoe was gliding along within a couple of feet of the bank, stealthily indeed and with diminished speed, lest the mere splash of the paddle should give the alarm. The bank was for the most part steep enough to afford complete concealment from any one at a short distance from the edge. It had just passed the spot, and was drawing away from the voices, when it suddenly stopped and swung round. But for a dexterous stroke of Boulanger's paddle it must have turned over, for it had come right across a long bramble that had become submerged.

"What was that?" exclaimed one of the New England men; "it sounded like a paddle."

"Sounded like a fiddlestick!" replied another; "you with your sharp ears are always hearing something that nobody else can, Master Dick."

"Well, I am not going to stop here any longer," said the first speaker. "We know that the Commandant of Fort Chambly has pushed forward detachments in this direction, and 'tis my belief that if we don't clear out, instead of shooting these Frenchmen and sending their despatches to the General at New York, we may get shot ourselves, or be taken and sent off to Montreal."

By this time Boulanger, feeling cautiously over the side, had come across the bramble that had stopped their course; his knife was through it in a moment and the canoe swung clear.

"Hush! I'll swear I heard a paddle this time, say what you like," cried the former speaker. "Run one of you to the creek and see that the canoes are all safe."

What else he may have said died away in the distance as the frail barque that carried Isidore and his companions stole swiftly away, and soon afterwards rounded a small headland and took to the open waters.

"All safe!" cried Boulanger. "Half an hour will bring us across to a point they could not reach on foot in three hours at least. We are out of rifle shot already, even if they should see us; so take it easy a little, my brave girl, whilst I look about and get my bearings all right."

Just for a moment the evening breeze wafted towards them a faint sound as of men shouting; then a shot was fired, but after that all became still. In half an hour they had crossed the lake, and on landing the guide ordered a halt and produced their supper.

"Our friends from Chambly are pretty certain to have reached St. Michel by this time if they are really moving in this direction," said Boulanger, as he shared the provisions among them. "We will rest a bit here and then push on; in any case there is, or used to be, an Indian settlement there, where we can take up our quarters for the night."

"Thank Heaven for that, on this poor child's account," replied Isidore. "From what you have told me I hope that her misfortunes will ensure her safety with any tribe of friendly Indians."

"Undoubtedly; but we will not talk of that now, nor think about it just yet, monsieur," whispered the guide, "or she will read it in our faces that we want to get rid of her, which may make the thing not quite so easy."

On starting again, to Isidore's great surprise, the guide quietly shouldered the canoe and marched off with it, though he subsequently allowed both Isidore and Amoahmeh to assist him in carrying it. A short hour's march brought them to another creek sufficiently large to float their skiff, and soon afterwards they came upon a second lake, which they traversed from end to end. Then, as they neared the shore, Isidore's ears were greeted by a well-known and most welcome sound—the challenge of a French sentinel. They had come upon the detachment sent out from Fort Chambly.

Great was the surprise of the French officer, who was in command of the little force, on seeing his friend Isidore at such a time and place and in such company. All this was of course quickly explained, and the young soldier and his guide were soon comfortably housed, but not until they had committed poor Amoahmeh, with many an expression of their gratitude for her kindly help, to the care of an Indian family, into whose wigwam she was received with all the awe that her infirmity was sure to command. It may well be believed that after such a day it was not long before all three were asleep and dreaming of old friends and old homes, either amid the grand and gloomy forests of the New World or the sunny slopes and smiling vineyards of the Old.

t sunrise on the following morning Isidore and his guide started for Chambly. Happily, Amoahmeh was still asleep. Accustomed as she was to the woods, the great distance they had traversed on the preceding day, and perhaps the excitement she had undergone, had told on her slight frame, and nature had insisted on her claim to a longer rest than usual. What the poor child's feelings may have been when she awoke and found herself once more alone in the world who shall say? Possibly the unwonted exercise of some still active faculties the day before had dulled her sensibility, for outwardly, at least, she seemed to have forgotten all the past, and went about as though she had never known any other home, and as though the strange faces that she saw around her had looked upon her all her life. But the earnest yet plaintively uttered, "Where are they?" no longer fell from her lips. It had been answered, and amid the darkness that enveloped that young loving soul, it may well be that there was one glimmering ray of light that kept some smouldering embers of reason still alive.

Isidore's mission was completed without further adventure, and after delivering his despatches at Chambly, and reporting to the commandant the particulars he had noted on his way thither, in conformity with General Montcalm's directions, he was ordered to proceed to Quebec on another service. This journey, although of about the same length as the previous one, was a much more easy affair, and was performed by water. Boulanger, however, who was now on his way home, still acted as guide, and day by day won more and more upon Isidore by his readiness and intelligence, and probably—though the young marquis might have been unwilling to own it—by his honest frankness and his outspoken dislike of everything mean and underhand. Even his remarks on passing events were listened to with a forbearance which they would hardly have met with from the Isidore de Beaujardin of a week ago.

In a few days Isidore and his guide reached Quebec, and there, notwithstanding the little occasional skirmishes that had taken place between them, they parted with regret, and with cordial expressions of good-will. The young soldier had had opportunity enough to see and appreciate the honest character of the Canadian, whilst the latter had been still more struck with the condescension as well as by the courage and endurance of the young noble, of whose high rank he was well aware, and whose almost necessarily courteous manner, even to his inferiors, formed a strong contrast to the overbearing and arbitrary behaviour of the Government officials with whom he generally had to deal.

Isidore's first proceeding was to report himself and deliver his despatches, on doing which he learned that although the intelligence of the capture of Oswego had arrived, no details had as yet been received, nor had his uncle, the Baron de Valricour, as yet reached Quebec. It was consequently not without hesitation that he made his way to the house of Madame de Rocheval, the lady with whom the daughter of Captain Lacroix was staying.

Isidore had never seen Marguerite Lacroix, but he took it for granted that it was she who, on his being shown into the drawing-room, rose from her embroidery frame to receive him.

"I am sorry, monsieur," said she, "that Madame de Rocheval is not at home. You have, doubtless, heard that news has been received of General Montcalm's having captured Oswego. Madame de Rocheval has a brother in one of the regiments about whom she is anxious, and my father, Captain Lacroix, who is quartered at Montreal, has not written either to me or to her for some time, so she has gone to the adjutant's office to——"

Here she paused; she would probably not have thought it necessary to offer all this explanation, but that her visitor seemed awkward and embarrassed, and she had continued speaking out of politeness. She stopped suddenly on perceiving, with a woman's quickness, that Isidore was evidently agitated or unwell.

"I beg your pardon, mademoiselle," said he, at last, but not without difficulty, "I have just come from Oswego."

"Indeed! Then you have passed through Montreal. Perhaps you have seen my father? He is very intimate with Monsieur de Valricour, who, I believe, is your uncle."

"Yes, yes, that is true, but—I had hoped that you might have already heard—that is, I did not suppose——" here Isidore stopped; and then, as he looked up and saw the half bewildered, half alarmed look that came over her face, he added, scarce audibly, "Now may God be merciful to you, my dear young lady, for the news that I bring will——"

"My father! my father!" was all that poor Marguerite could utter, as, with hands clasped together, she bent forward in an agony of suspense.

"He is at rest, my dear young lady," said Isidore, with as much calmness as he could command. "He fell in the moment of victory, as a brave soldier like him would wish to do."

Marguerite uttered a cry that went to Isidore's heart. He stepped forward just in time, for, had he not caught her in his arms, she would have fallen to the ground insensible. At this moment they were joined by Madame de Rocheval, who had returned in haste, having heard in the town the news of Captain Lacroix's death; the fainting girl was carried to her room, and Isidore, after hurriedly explaining to Madame de Rocheval the circumstances that had brought him there, quitted the house, promising to call on the following day.

On the morrow letters arrived from the Baron de Valricour, who had come down from Oswego to Montreal, but was compelled to remain there. They contained the news of his friend's death, and also an assurance of his intention to fulfil the promise which he had given to Marguerite's father. It remained for Isidore, however, to give to the poor orphan girl that which in this direst of all trials we all so earnestly yearn after, the personal account of one who has himself seen the dear one laid to his last rest, and to present to her the little relic he had himself meant to keep in memory of his fellow-soldier—the blood-stained strip of a flag in which, by Isidore's directions, they had carried the hero to his grave.

After the lapse of another week Monsieur de Valricour was able to resume his journey and reach Quebec, when he took Marguerite under his guardianship, arranging that she should stay with Madame de Rocheval until such time as he might be able to take her to France. He brought with him Isidore's appointment as one of the aides-de-camp to General Montcalm, who, already prepossessed in his favour by his coolness and courage at Oswego, had been particularly pleased with the report he had subsequently made on the line of country between Oswego and Lake Champlain.

"How strange it is"—such was part of Isidore's musings as the next day he passed out of the old Porte St. Louis on his road to Montcalm's head-quarters up the country—"how strange it is that one should feel such regret at parting from people like Madame Rocheval and that poor girl, whom one never set eyes on till within a week or two! I daresay, too, that I shall never see them again. It seems a pity to make friends, if only to part with them so soon, and perhaps forget them just as quickly, or at all events only to be forgotten by them."

Canadian winter, with the thermometer frequently standing at forty, and sometimes even fifty or sixty degrees below the freezing point of Fahrenheit, with its rivers completely blocked by ice and its fields covered by several feet of snow, puts a stop to most operations, whether mercantile or military. The winter of 1756 consequently afforded Isidore de Beaujardin, in his comfortable quarters at Montreal, complete leisure to reflect upon the incidents that had occurred during the last few months of his life, amongst which his short visit to Quebec occupied a prominent place in his reveries and meditations.