Project Gutenberg's Select Temperance Tracts, by American Tract Society This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Select Temperance Tracts Author: American Tract Society Release Date: November 4, 2008 [EBook #27146] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SELECT TEMPERANCE TRACTS *** Produced by Bryan Ness, Deirdre M., and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from scans of public domain works at the University of Michigan's Making of America collection.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible; please see detailed list of printing issues at the end of the text. The orginal page numbering of each tract has been maintained; for ease of reference, the preparer of the e-text has assigned each tract a letter, and appended the identifying letters to the original page numbers.

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY, 150 NASSAU-STREET, NEW YORK.

| Pages | ||

|---|---|---|

| EFFECTS OF ARDENT SPIRITS. By Dr. Rush | 8 | [A] |

| TRAFFIC IN ARDENT SPIRITS. By Rev. Dr. Edwards | 32 | [B] |

| REWARDS OF DRUNKENNESS | 4 | [C] |

| THE WELL-CONDUCTED FARM | 12 | [D] |

| KITTREDGE’S ADDRESS ON EFFECTS OF ARDENT SPIRITS | 24 | [E] |

| DICKINSON’S APPEAL TO YOUTH | 8 | [F] |

| ALARM TO DISTILLERS AND THEIR ALLIES | 8 | [G] |

| PUTNAM AND THE WOLF | 24 | [H] |

| HITCHCOCK ON THE MANUFACTURE OF ARDENT SPIRITS | 28 | [I] |

| M’ILVAINE’S ADDRESS TO YOUNG MEN | 24 | [J] |

| WHO SLEW ALL THESE? | 4 | [K] |

| SEWALL ON INTEMPERANCE | 24 | [L] |

| BIBLE ARGUMENT FOR TEMPERANCE | 12 | [M] |

| FOUR REASONS AGAINST THE USE OF ALCOHOLIC LIQUORS | 12 | [N] |

| DEBATES OF CONSCIENCE ON ARDENT SPIRITS | 16 | [O] |

| BARNES ON TRAFFIC IN ARDENT SPIRITS | 24 | [P] |

| THE FOOLS’ PENCE | 8 | [Q] |

| THE POOR MAN’S HOUSE REPAIRED | 12 | [R] |

| JAMIE; OR A WORD FROM IRELAND FOR TEMPERANCE | 16 | [S] |

| THE WONDERFUL ESCAPE | 4 | [T] |

| THE EVENTFUL TWELVE HOURS | 16 | [U] |

| THE LOST MECHANIC RESTORED | 4 | [V] |

| REFORMATION OF DRUNKARDS | 4 | [W] |

| TOM STARBOARD AND JACK HALYARD | 24 | [X] |

| THE OX SERMON | 8 | [Y] |

By ardent spirits, I mean those liquors only which are obtained by distillation from fermented substances of any kind. To their effects upon the bodies and minds of men, the following inquiry shall be exclusively confined.

The effects of ardent spirits divide themselves into such as are of a prompt, and such as are of a chronic nature. The former discover themselves in drunkenness; and the latter in a numerous train of diseases and vices of the body and mind.

I. I shall begin by briefly describing their prompt or immediate effects in a fit of drunkenness.

This odious disease—for by that name it should be called—appears with more or less of the following symptoms, and most commonly in the order in which I shall enumerate them.

1. Unusual garrulity.

2. Unusual silence.

3. Captiousness, and a disposition to quarrel.

4. Uncommon good-humor, and an insipid simpering, or laugh.

5. Profane swearing and cursing.

6. A disclosure of their own or other people’s secrets.

7. A rude disposition to tell those persons in company whom they know, their faults.

8. Certain immodest actions. I am sorry to say this sign of the first stage of drunkenness sometimes appears in women, who, when sober, are uniformly remarkable for chaste and decent manners.

9. A clipping of words.

10. Fighting; a black eye, or a swelled nose, often mark this grade of drunkenness.

11. Certain extravagant acts which indicate a temporary fit of madness. Those are singing, hallooing, roaring, imitating the noises of brute animals, jumping, tearing off clothes, dancing naked, breaking glasses and china, and dashing other articles of household furniture upon the ground or floor. After a while the paroxysm of drunkenness is completely formed. The face now becomes flushed, the eyes project, and are somewhat watery, winking is less frequent than is natural; the under lip is protruded—the head inclines a little to one shoulder—the jaw falls—belchings and hiccough take place—the limbs totter—the whole body staggers. The unfortunate subject of this history next falls on his seat—he looks around him with a vacant countenance, and mutters inarticulate sounds to himself—he attempts to rise and walk: in this attempt he falls upon his side, from which he gradually turns upon his back: he now closes his eyes and falls into a profound sleep, frequently attended with snoring, and profuse sweats, and sometimes with such a relaxation of the muscles which confine the bladder and the lower bowels, as to produce a symptom which delicacy forbids me to mention. In this condition he often lies from ten, twelve, and twenty-four hours, to two, three, four, and five days, an object of pity and disgust to his family and friends. His recovery from this fit of intoxication is marked with several peculiar appearances. He opens his eyes and closes them again—he gapes and stretches his limbs—he then coughs and pukes—his voice is hoarse—he rises with difficulty, and staggers to a chair—his eyes resemble balls of fire—his hands tremble—he loathes the sight of food—he calls for a glass of spirits to compose his stomach—now and then he emits a deep-fetched sigh, or groan, from a transient twinge of conscience; but he more frequently scolds, and curses every thing around him. In this stage of languor and stupidity he remains for two or three days, before he is able to resume his former habits of business and conversation.

Pythagoras, we are told, maintained that the souls of men after death expiated the crimes committed by them in this world, by animating certain brute animals; and that the souls of those animals, in their turns, entered into men, and carried with them all their peculiar qualities[3, A] and vices. This doctrine of one of the wisest and best of the Greek philosophers, was probably intended only to convey a lively idea of the changes which are induced in the body and mind of man by a fit of drunkenness. In folly, it causes him to resemble a calf—in stupidity, an ass—in roaring, a mad bull—in quarrelling and fighting, a dog—in cruelty, a tiger—in fetor, a skunk—in filthiness, a hog—and in obscenity, a he-goat.

It belongs to the history of drunkenness to remark, that its paroxysms occur, like the paroxysms of many diseases, at certain periods, and after longer or shorter intervals. They often begin with annual, and gradually increase in their frequency, until they appear in quarterly, monthly, weekly, and quotidian or daily periods. Finally, they afford scarcely any marks of remission, either during the day or the night. There was a citizen of Philadelphia, many years ago, in whom drunkenness appeared in this protracted form. In speaking of him to one of his neighbors, I said, “Does he not sometimes get drunk?” “You mean,” said his neighbor, “is he not sometimes sober?”

It is further remarkable, that drunkenness resembles certain hereditary, family, and contagious diseases. I have once known it to descend from a father to four out of five of his children. I have seen three, and once four brothers, who were born of sober ancestors, affected by it; and I have heard of its spreading through a whole family composed of members not originally related to each other. These facts are important, and should not be overlooked by parents, in deciding upon the matrimonial connections of their children.

II. Let us next attend to the chronic effects of ardent spirits upon the body and mind. In the body they dispose to every form of acute disease; they moreover excite fevers in persons predisposed to them from other causes. This has been remarked in all the yellow-fevers which have visited the cities of the United States. Hard-drinkers seldom escape, and rarely recover from them. The following diseases are the usual consequences of the habitual use of ardent spirits:

1. A decay of appetite, sickness at stomach, and a puking of bile, or a discharge of a frothy and viscid phlegm, by hawking, in the morning.

2. Obstructions of the liver. The fable of Prometheus, on whose liver a vulture was said to prey constantly, as a punishment for his stealing fire from heaven, was intended to illustrate the painful effects of ardent spirits upon that organ of the body.

3. Jaundice, and dropsy of the belly and limbs, and finally of every cavity in the body. A swelling in the feet and legs is so characteristic a mark of habits of intemperance, that the merchants in Charleston, I have been told, cease to trust the planters of South Carolina as soon as they perceive it. They very naturally conclude industry and virtue to be extinct in that man, in whom that symptom of disease has been produced by the intemperate use of distilled spirits.

4. Hoarseness, and a husky cough, which often terminate in consumption, and sometimes in an acute and fatal disease of the lungs.

5. Diabetes, that is, a frequent and weakening discharge of pale or sweetish urine.

6. Redness, and eruptions on different parts of the body. They generally begin on the nose, and after gradually extending all over the face, sometimes descend to the limbs in the form of leprosy. They have been called “rum-buds,” when they appear in the face. In persons who have occasionally survived these effects of ardent spirits on the skin, the face after a while becomes bloated, and its redness is succeeded by a death-like paleness. Thus, the same fire which produces a red color in iron, when urged to a more intense degree, produces what has been called a white-heat.

7. A fetid breath, composed of every thing that is offensive in putrid animal matter.

8. Frequent and disgusting belchings. Dr. Haller relates the case of a notorious drunkard having been suddenly destroyed, in consequence of the vapor discharged from his stomach by belching, accidentally taking fire by coming in contact with the flame of a candle.

9. Epilepsy.

10. Gout, in all its various forms of swelled limbs, colic, palsy, and apoplexy.

11. Lastly, madness. The late Dr. Waters, while he acted as house-pupil and apothecary of the Pennsylvania[5, A] hospital, assured me, that in one-third of the patients confined by this terrible disease, it had been induced by ardent spirits.

Most of the diseases which have been enumerated are of a mortal nature. They are more certainly induced, and terminate more speedily in death, when spirits are taken in such quantities, and at such times, as to produce frequent intoxication; but it may serve to remove an error with which some intemperate people console themselves, to remark, that ardent spirits often bring on fatal diseases without producing drunkenness. I have known many persons destroyed by them who were never completely intoxicated during the whole course of their lives. The solitary instances of longevity which are now and then met with in hard-drinkers, no more disprove the deadly effects of ardent spirits, than the solitary instances of recoveries from apparent death by drowning, prove that there is no danger to life from a human body lying an hour or two under water.

The body, after its death from the use of distilled spirits, exhibits, by dissection, certain appearances which are of a peculiar nature. The fibres of the stomach and bowels are contracted—abscesses, gangrene, and schirri are found in the viscera. The bronchial vessels are contracted—the bloodvessels and tendons in many parts of the body are more or less ossified, and even the hair of the head possesses a crispness which renders it less valuable to wig-makers than the hair of sober people.

Not less destructive are the effects of ardent spirits upon the human mind. They impair the memory, debilitate the understanding, and pervert the moral faculties. It was probably from observing these effects of intemperance in drinking upon the mind, that a law was formerly passed in Spain which excluded drunkards from being witnesses in a court of justice. But the demoralizing effects of distilled spirits do not stop here. They produce not only falsehood, but fraud, theft, uncleanliness, and murder. Like the demoniac mentioned in the New Testament, their name is “Legion,” for they convey into the soul a host of vices and crimes.

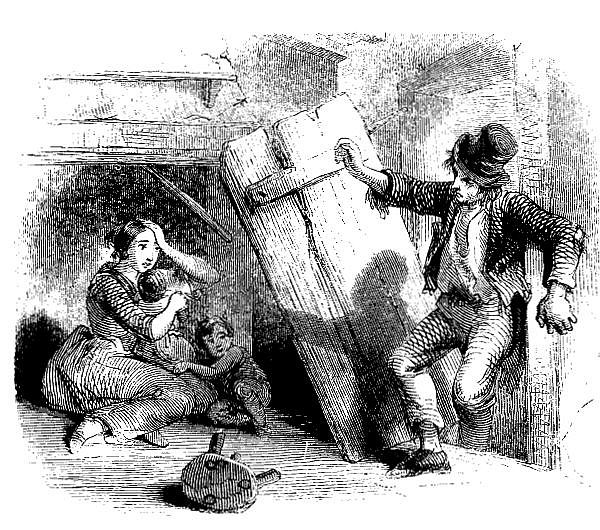

A more affecting spectacle cannot be exhibited than a person into whom this infernal spirit, generated by habits[6, A] of intemperance, has entered: it is more or less affecting, according to the station the person fills in a family, or in society, who is possessed by it. Is he a husband? How deep the anguish which rends the bosom of his wife! Is she a wife? Who can measure the shame and aversion which she excites in her husband? Is he the father, or is she the mother of a family of children? See their averted looks from their parent, and their blushing looks at each other. Is he a magistrate? or has he been chosen to fill a high and respectable station in the councils of his country? What humiliating fears of corruption in the administration of the laws, and of the subversion of public order and happiness, appear in the countenances of all who see him. Is he a minister of the gospel? Here language fails me. If angels weep, it is at such a sight.

In pointing out the evils produced by ardent spirits, let us not pass by their effects upon the estates of the persons who are addicted to them. Are they inhabitants of cities? Behold their houses stripped gradually of their furniture, and pawned, or sold by a constable, to pay tavern debts. See their names upon record in the dockets of every court, and whole pages of newspapers filled with advertisements of their estates for public sale. Are they inhabitants of country places? Behold their houses with shattered windows—their barns with leaky roofs—their gardens overrun with weeds—their fields with broken fences—their hogs without yokes—their sheep without wool—their cattle and horses without fat—and their children, filthy and half-clad, without manners, principles, and morals. This picture of agricultural wretchedness is seldom of long duration. The farms and property thus neglected and depreciated, are seized and sold for the benefit of a group of creditors. The children that were born with the prospect of inheriting them, are bound out to service in the neighborhood; while their parents, the unworthy authors of their misfortunes, ramble into new and distant settlements, alternately fed on their way by the hand of charity, or a little casual labor.

Thus we see poverty and misery, crimes and infamy, diseases and death, are all the natural and usual consequences of the intemperate use of ardent spirits.

I have classed death among the consequences of hard drinking. But it is not death from the immediate hand of[7, A] the Deity, nor from any of the instruments of it which were created by him: it is death from suicide. Yes, thou poor degraded creature who art daily lifting the poisoned bowl to thy lips, cease to avoid the unhallowed ground in which the self-murderer is interred, and wonder no longer that the sun should shine, and the rain fall, and the grass look green upon his grave. Thou art perpetrating gradually, by the use of ardent spirits, what he has effected suddenly by opium or a halter. Considering how many circumstances from surprise, or derangement, may palliate his guilt, or that, unlike yours, it was not preceded and accompanied by any other crime, it is probable his condemnation will be less than yours at the day of judgment.

I shall now take notice of the occasions and circumstances which are supposed to render the use of ardent spirits necessary, and endeavor to show that the arguments in favor of their use in such cases are founded in error, and that in each of them ardent spirits, instead of affording strength to the body, increase the evils they are intended to relieve.

1. They are said to be necessary in very cold weather. This is far from being true, for the temporary warmth they produce is always succeeded by a greater disposition in the body to be affected by cold. Warm dresses, a plentiful meal just before exposure to the cold, and eating occasionally a little gingerbread, or any other cordial food, is a much more durable method of preserving the heat of the body in cold weather.

2. They are said to be necessary in very warm weather. Experience proves that they increase, instead of lessening the effects of heat upon the body, and thereby dispose to diseases of all kinds. Even in the warm climate of the West Indies, Dr. Bell asserts this to be true. “Rum,” says this author, “whether used habitually, moderately, or in excessive quantities, in the West Indies, always diminishes the strength of the body, and renders men more susceptible of disease, and unfit for any service in which vigor or activity is required.”[A] As well might we throw oil into a house, the roof of which was on fire, in order to[8, A] prevent the flames from extending to its inside, as pour ardent spirits into the stomach to lessen the effects of a hot sun upon the skin.

3. Nor do ardent spirits lessen the effects of hard labor upon the body. Look at the horse, with every muscle of his body swelled from morning till night in the plough, or a team; does he make signs for a draught of toddy, or a glass of spirits, to enable him to cleave the ground, or to climb a hill? No; he requires nothing but cool water and substantial food. There is no nourishment in ardent spirits. The strength they produce in labor is of a transient nature, and is always followed by a sense of weakness and fatigue.

Every man is in danger of becoming a drunkard who is in the habit of drinking ardent spirits—1. When he is warm. 2. When he is cold. 3. When he is wet. 4. When he is dry. 5. When he is dull. 6. When he is lively. 7. When he travels. 8. When he is at home. 9. When he is in company. 10. When he is alone. 11. When he is at work. 12. When he is idle. 13. Before meals. 14. After meals. 15. When he gets up. 16. When he goes to bed. 17. On holidays. 18. On public occasions. 19. On any day; or, 20. On any occasion.

[A] See his “Inquiry into the Causes which Produce, and the Means of Preventing Diseases among British Officers, Soldiers, and others, in the West Indies.”

Ardent spirit is composed of alcohol and water, in nearly equal proportions. Alcohol is composed of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen, in the proportion of about fourteen, fifty-two, and thirty-four parts to the hundred. It is, in its nature, as manifested by its effects, a poison. When taken in any quantity it disturbs healthy action in the human system, and in large doses suddenly destroys life. It resembles opium in its nature, and arsenic in its effects. And though when mixed with water, as in ardent spirit, its evils are somewhat modified, they are by no means prevented. Ardent spirit is an enemy to the human constitution, and cannot be used as a drink without injury. Its ultimate tendency invariably is, to produce weakness, not strength; sickness, not health; death, not life.

Consequently, to use it is an immorality. It is a violation of the will of God, and a sin in magnitude equal to all the evils, temporal and eternal, which flow from it. Nor can the furnishing of ardent spirit for the use of others be accounted a less sin, inasmuch as this tends to produce evils greater than for an individual merely to drink it. And if a man knows, or has the opportunity of knowing, the nature and effects of the traffic in this article, and yet continues to[2, B] be engaged in it, he may justly be regarded as an immoral man; and for the following reasons, viz.

Ardent spirit, as a drink, is not needful. All men lived without it, and all the business of the world was conducted without it, for thousands of years. It is not three hundred years since it began to be generally used as a drink in Great Britain, nor one hundred years since it became common in America. Of course it is not needful.

It is not useful. Those who do not use it are, other things being equal, in all respects better than those who do. Nor does the fact that persons have used it with more or less frequency, in a greater or smaller quantity, for a longer or shorter time, render it either needful, or useful, or harmless, or right for them to continue to use it. More than a million of persons in this country, and multitudes in other countries, who once did use it, and thought it needful, have, within five years, ceased to use it, and they have found that they are in all respects better without it. And this number is so great, of all ages, and conditions, and employments, as to render it certain, should the experiment be fairly made, that this would be the case with all. Of course, ardent spirit, as a drink, is not useful.

It is hurtful. Its whole influence is injurious to the body and the mind for this world and the world to come.

1. It forms an unnecessary, artificial, and very dangerous appetite; which, by gratification, like the desire for sinning, in the man who sins, tends continually to increase. No man can form this appetite without increasing his danger of dying a drunkard, and exerting an influence which tends to perpetuate drunkenness, and all its abominations, to the end of the world. Its very formation, therefore, is a violation of the will of God. It is, in its nature, an immorality, and springs from an inordinate desire of a kind or degree of bodily enjoyment—animal gratification, which God has shown to be inconsistent with his glory, and the highest[3, B] good of man. It shows that the person who forms it is not satisfied with the proper gratification of those appetites and passions which God has given him, or with that kind and degree of bodily enjoyment which infinite wisdom and goodness have prescribed as the utmost that can be possessed consistently with a person’s highest happiness and usefulness, the glory of his Maker, and the good of the universe. That person covets more animal enjoyment; to obtain it he forms a new appetite, and in doing this he rebels against God.

That desire for increased animal enjoyment from which rebellion springs is sin, and all the evils which follow in its train are only so many voices by which Jehovah declares “the way of transgressors is hard.” The person who has formed an appetite for ardent spirit, and feels uneasy if he does not gratify it, has violated the divine arrangement, disregarded the divine will, and if he understands the nature of what he has done, and approves of it, and continues in it, it will ruin him. He will show that there is one thing in which he will not have God to reign over him. And should he keep the whole law, and yet continue knowingly, habitually, wilfully, and perseveringly to offend in that one point, he will perish. Then, and then only, according to the Bible, can any man be saved, when he has respect to all the known will of God, and is disposed to be governed by it. He must carry out into practice, with regard to the body and the soul, “Not my will, but thine be done.” His grand object must be, to know the will of God, and when he knows it, to be governed by it, and with regard to all things. This, the man who is not contented with that portion of animal enjoyment which the proper gratification of the appetites and passions which God has given him will afford, but forms an appetite for ardent spirit, or continues to gratify it after it is formed, does not do. In this respect, if he understands the nature and effects of his actions, he prefers his own will to the known will of God, and is ripening to hear, from the lips[4, B] of his Judge, “Those mine enemies, that would not that I should reign over them, bring them hither and slay them before me.” And the men who traffic in this article, or furnish it as a drink for others, are tempting them to sin, and thus uniting their influence with that of the devil for ever to ruin them. This is an aggravated immorality, and the men who continue to do it are immoral men.

2. The use of ardent spirit, to which the traffic is accessory, causes a great and wicked waste of property. All that the users pay for this article is to them lost, and worse than lost. Should the whole which they use sink into the earth, or mingle with the ocean, it would be better for them, and better for the community, than for them to drink it. All which it takes to support the paupers, and prosecute the crimes which ardent spirit occasions, is, to those who pay the money, utterly lost. All the diminution of profitable labor which it occasions, through improvidence, idleness, dissipation, intemperance, sickness, insanity, and premature deaths, is to the community so much utterly lost. And these items, as has often been shown, amount in the United States to more than $100,000,000 a year. To this enormous and wicked waste of property, those who traffic in the article are knowingly accessory.

A portion of what is thus lost by others, they obtain themselves; but without rendering to others any valuable equivalent. This renders their business palpably unjust; as really so as if they should obtain that money by gambling; and it is as really immoral. It is also unjust in another respect: it burdens the community with taxes both for the support of pauperism, and for the prosecution of crimes, and without rendering to that community any adequate compensation. These taxes, as shown by facts, are four times as great as they would be if there were no sellers of ardent spirit. All the profits, with the exception perhaps of a mere pittance which he pays for license, the seller puts into his[5, B] own pocket, while the burdens are thrown upon the community. This is palpably unjust, and utterly immoral. Of 1,969 paupers in different almshouses in the United States, 1,790, according to the testimony of the overseers of the poor, were made such by spirituous liquor. And of 1,764 criminals in different prisons, more than 1,300 were either intemperate men, or were under the power of intoxicating liquor when the crimes for which they were imprisoned were committed. And of 44 murders, according to the testimony of those who prosecuted or conducted the defence of the murderers, or witnessed their trials, 43 were committed by intemperate men, or upon intemperate men, or those who at the time of the murder were under the power of strong drink.

The Hon. Felix Grundy, United States senator from Tennessee, after thirty years’ extensive practice as a lawyer, gives it as his opinion that four-fifths of all the crimes committed in the United States can be traced to intemperance. A similar proportion is stated, from the highest authority, to result from the same cause in Great Britain. And when it is considered that more than 200 murders are committed, and more than 100,000 crimes are prosecuted in the United States in a year, and that such a vast proportion of them are occasioned by ardent spirit, can a doubt remain on the mind of any sober man, that the men who know these facts, and yet continue to traffic in this article, are among the chief causes of crime, and ought to be viewed and treated as immoral men? It is as really immoral for a man, by doing wrong, to excite others to commit crimes, as to commit them himself; and as really unjust wrongfully to take another’s property with his consent, as without it. And though it might not be desirable to have such a law, yet no law in the statute-book is more righteous than one which should require that those who make paupers should support them, and those who excite others to commit crimes, should pay the cost of their prosecution, and should, with those who[6, B] commit them, bear all the evils. And so long as this is not the case they will be guilty, according to the divine law, of defrauding, as well as tempting and corrupting their fellow-men. And though such crimes cannot be prosecuted, and justice be awarded in human courts, their perpetrators will be held to answer, and will meet with full and awful retribution at the divine tribunal. And when judgment is laid to the line, and righteousness to the plummet, they will appear as they really are, criminals, and will be viewed and treated as such for ever.

There is another view in which the traffic in ardent spirit is manifestly highly immoral. It exposes the children of those who use it, in an eminent degree, to dissipation and crime. Of 690 children prosecuted and imprisoned for crimes, more than 400 were from intemperate families. Thus the venders of this liquor exert an influence which tends strongly to ruin not only those who use it, but their children; to render them far more liable to idleness, profligacy, and ruin, than the children of those who do not use it; and through them to extend these evils to others, and to perpetuate them to future generations. This is a sin of which all who traffic in ardent spirit are guilty. Often the deepest pang which a dying parent feels for his children, is lest, through the instrumentality of such men, they should be ruined. And is it not horrible wickedness for them, by exposing for sale one of the chief causes of this ruin, to tempt them in the way to death? If he who takes money from others without an equivalent, or wickedly destroys property, is an immoral man, what is he who destroys character, who corrupts children and youth, and exerts an influence to extend and perpetuate immorality and crime through future generations? This every vender of ardent spirit does; and if he continues in this business with a knowledge of the subject, it marks him as an habitual and persevering violater of the will of God.

3. Ardent spirit impairs, and often destroys reason. Of 781 maniacs in different insane hospitals, 392, according to the testimony of their own friends, were rendered maniacs by strong drink. And the physicians who had the care of them gave it as their opinion, that this was the case with many of the others. Those who have had extensive experience, and the best opportunities for observation with regard to this malady, have stated, that probably from one-half to three-fourths of the cases of insanity, in many places, are occasioned in the same way. Ardent spirit is a poison so diffusive and subtile that it is found, by actual experiment, to penetrate even the brain.

Dr. Kirk, of Scotland, dissected a man a few hours after death who died in a fit of intoxication; and from the lateral ventricles of the brain he took a fluid distinctly visible to the smell as whiskey; and when he applied a candle to it in a spoon, it took fire and burnt blue; “the lambent blue flame,” he says, “characteristic of the poison, playing on the surface of the spoon for some seconds.”

It produces also, in the children of those who use it freely, a predisposition to intemperance, insanity, and various diseases of both body and mind, which, if the cause is continued, becomes hereditary, and is transmitted from generation to generation; occasioning a diminution of size, strength, and energy, a feebleness of vision, a feebleness and imbecility of purpose, an obtuseness of intellect, a depravation of moral taste, a premature old age, and a general deterioration of the whole character. This is the case in every country, and in every age.

Instances are known where the first children of a family, who were born when their parents were temperate, have been healthy, intelligent, and active; while the last children, who were born after the parents had become intemperate, were dwarfish and idiotic. A medical gentleman writes, “I have no doubt that a disposition to nervous diseases of a[8, B] peculiar character is transmitted by drunken parents.” Another gentleman states that, in two families within his knowledge, the different stages of intemperance in the parents seemed to be marked by a corresponding deterioration in the bodies and minds of the children. In one case, the eldest of the family is respectable, industrious, and accumulates property; the next is inferior, disposed to be industrious, but spends all he can earn in strong drink. The third is dwarfish in body and mind, and, to use his own language, “a poor, miserable remnant of a man.”

In another family of daughters, the first is a smart, active girl, with an intelligent, well-balanced mind; the others are afflicted with different degrees of mental weakness and imbecility, and the youngest is an idiot. Another medical gentleman states, that the first child of a family, who was born when the habits of the mother were good, was healthy and promising; while the four last children, who were born after the mother had become addicted to the habit of using opium, appeared to be stupid; and all, at about the same age, sickened and died of a disease apparently occasioned by the habits of the mother.

Another gentleman mentions a case more common, and more appalling still. A respectable and influential man early in life adopted the habit of using a little ardent spirit daily, because, as he thought, it did him good. He and his six children, three sons and three daughters, are now in the drunkard’s grave, and the only surviving child is rapidly following in the same way, to the same dismal end.

The best authorities attribute one-half the madness, three-fourths of the pauperism, end four-fifths of the crimes and wretchedness in Great Britain to the use of strong drink.

4. Ardent spirit increases the number, frequency, and violence of diseases, and tends to bring those who use it to a premature grave. In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, of about 7,500 people, twenty-one persons were killed by it in[9, B] a year. In Salem, Massachusetts, of 181 deaths, twenty were occasioned in the same way. Of ninety-one adults who died in New Haven, Connecticut, in one year, thirty-two, according to the testimony of the Medical Association, were occasioned, directly or indirectly, by strong drink, and a similar proportion had been occasioned by it in previous years. In New Brunswick, New Jersey, of sixty-seven adult deaths in one year, more than one-third were caused by intoxicating liquor. In Philadelphia, of 4,292 deaths, 700 were, in the opinion of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, caused in the same way. The physicians of Annapolis, Maryland, state that, of thirty-two persons, male and female, who died in 1828, above eighteen years of age, ten, or nearly one-third, died of diseases occasioned by intemperance; that eighteen were males, and that of these, nine, or one-half, died of intemperance. They also say, “When we recollect that even the temperate use, as it is called, of ardent spirits, lays the foundation of a numerous train of incurable maladies, we feel justified in expressing the belief, that were the use of distilled liquors entirely discontinued, the number of deaths among the male adults would be diminished at least one-half.”

Says an eminent physician, “Since our people generally have given up the use of spirit, they have not had more than half as much sickness as they had before; and I have no doubt, should all the people of the United States cease to use it, that nearly half the sickness of the country would cease.” Says another, after forty years’ extensive practice, “Half the men every year who die of fevers might recover, had they not been in the habit of using ardent spirit. Many a man, down for weeks with a fever, had he not used ardent spirit, would not have been confined to his house a day. He might have felt a slight headache, but a little fasting would have removed the difficulty, and the man been well. And many a man who was never intoxicated, when visited with[10, B] a fever, might be raised up as well as not, were it not for that state of the system which daily moderate drinking occasions, who now, in spite of all that can be done, sinks down and dies.”

Nor are we to admit for a moment the popular reasoning, as applicable here, “that the abuse of a thing is no argument against its use;” for, in the language of the late Secretary of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Philadelphia, Samuel Emlen, M. D., “All use of ardent spirits,” i. e. as a drink, “is an abuse. They are mischievous under all circumstances.” Their tendency, says Dr. Frank, when used even moderately, is to induce disease, premature old age, and death. And Dr. Trotter states, that no cause of disease has so wide a range, or so large a share, as the use of spirituous liquors.

Dr. Harris states, that the moderate use of spirituous liquors has destroyed many who were never drunk; and Dr. Kirk gives it as his opinion, that men who were never considered intemperate, by daily drinking have often shortened life more than twenty years; and that the respectable use of this poison kills more men than even drunkenness. Dr. Wilson gives it as his opinion, that the use of spirit in large cities causes more diseases than confined air, unwholesome exhalations, and the combined influence of all other evils.

Dr. Cheyne, of Dublin, Ireland, after thirty years’ practice and observation, gives it as his opinion, that should ten young men begin at twenty-one years of age to use but one glass of two ounces a day, and never increase the quantity, nine out of ten would shorten life more than ten years. But should moderate drinkers shorten life only five years, and drunkards only ten, and should there be but four moderate drinkers to one drunkard, it would in thirty years cut off in the United States 32,400,000 years of human life. An aged physician in Maryland states, that when the fever[11, B] breaks out there, the men who do not use ardent spirit are not half as likely as other men to have it; and that if they do have it, they are ten times as likely to recover. In the island of Key West, on the coast of Florida, after a great mortality, it was found that every person who had died had been in the habit of using ardent spirit. The quantity used was afterwards diminished more than nine-tenths, and the inhabitants became remarkably healthy.

A gentleman of great respectability from the south, states, that those who fall victims to southern climes, are almost invariably addicted to the free use of ardent spirit. Dr. Mosely, after a long residence in the West Indies, declares, “that persons who drink nothing but cold water, or make it their principal drink, are but little affected by tropical climates; that they undergo the greatest fatigue without inconvenience, and are not so subject as others to dangerous diseases;” and Dr. Bell, “that rum, when used even moderately, always diminishes the strength, and renders men more susceptible of disease; and that we might as well throw oil into a house, the roof of which is on fire, in order to prevent the flames from extending to the inside, as to pour ardent spirits into the stomach to prevent the effect of a hot sun upon the skin.”

Of seventy-seven persons found dead in different regions of country, sixty-seven, according to the coroners’ inquests, were occasioned by strong drink. Nine-tenths of those who die suddenly after the drinking of cold water, have been habitually addicted to the free use of ardent spirit; and that draught of cold water, that effort, or fatigue, or exposure to the sun, or disease, which a man who uses no ardent spirit will bear without inconvenience or danger, will often kill those who use it. Their liability to sickness and to death is often increased tenfold. And to all these evils, those who continue to traffic in it, after all the light which God in his providence has thrown upon the subject, are[12, B] knowingly accessory. Whether they deal in it by whole sale or retail, by the cargo or the glass, they are, in their influence, drunkard-makers. So are also those who furnish the materials; those who advertise the liquors, and thus promote their circulation; those who lease their tenements to be employed as dram-shops, or stores for the sale of ardent spirit; and those also who purchase their groceries of spirit dealers rather than of others, for the purpose of saving to the amount which the sale of ardent spirit enables such men, without loss, to undersell their neighbors. These are all accessory to the making of drunkards, and as such will be held to answer at the divine tribunal. So are those men who employ their shipping in transporting the liquors, or are in any way knowingly aiding and abetting in perpetuating their use as a drink in the community.

It is estimated that four-fifths of those who were swept away by the late direful visitation of cholera, were such as had been addicted to the use of intoxicating drink. Dr. Bronson, of Albany, who spent some time in Canada, and whose professional character and standing give great weight to his opinions, says, “Intemperance of any species, but particularly intemperance in the use of distilled liquors, has been a more productive cause of cholera than any other, and indeed than all others.” And can men, for the sake of money, make it a business knowingly and perseveringly to furnish the most productive cause of cholera, and not be guilty of blood—not manifest a recklessness of character which will brand the mark of vice and infamy on their foreheads? “Drunkards and tipplers,” he adds, “have been searched out with such unerring certainty as to show that the arrows of death have not been dealt out with indiscrimination. An indescribable terror has spread through the ranks of this class of beings. They see the bolts of destruction aimed at their heads, and every one calls himself a victim. There seems to be a natural affinity between[13, B] cholera and ardent spirit.” What, then, in days of exposure to this malady, is so great a nuisance as the places which furnish this poison? Says Dr. Rhinelander, who, with Dr. De Kay, was deputed from New York to visit Canada, “We may be asked who are the victims of this disease? I answer, the intemperate it invariably cuts off.” In Montreal, after 1,200 had been attacked, a Montreal paper states, that “not a drunkard who has been attacked has recovered of the disease, and almost all the victims have been at least moderate drinkers.” In Paris, the 30,000 victims were, with few exceptions, those who freely used intoxicating liquors. Nine-tenths of those who died of the cholera in Poland were of the same class.

In St. Petersburgh and Moscow, the average number of deaths in the bills of mortality, during the prevalence of the cholera, when the people ceased to drink brandy, was no greater than when they used it during the usual months of health—showing that brandy, and attendant dissipation, killed as many people in the same time as even the cholera itself, that pestilence which has spread sackcloth over the nations. And shall the men who know this, and yet continue to furnish it for all who can be induced to buy, escape the execration of being the destroyers of their race? Of more than 1,000 deaths in Montreal, it is stated that only two were members of Temperance societies. It was also stated, that as far as was known no members of Temperance societies in Ireland, Scotland, or England, had yet fallen victims to that dreadful disease.

From Montreal, Dr. Bronson writes, “Cholera has stood up here, as it has done everywhere, the advocate of Temperance. It has pleaded most eloquently, and with tremendous effect. The disease has searched out the haunt of the drunkard, and has seldom left it without bearing away its victim. Even moderate drinkers have been but little better off. Ardent spirits, in any shape, and in all[14, B] quantities, have been highly detrimental. Some temperate men resorted to them during the prevalence of the malady as a preventive, or to remove the feeling of uneasiness about the stomach, or for the purpose of drowning their apprehensions, but they did it at their peril.”

Says the London Morning Herald, after stating that the cholera fastens its deadly grasp upon this class of men, “The same preference for the intemperate and uncleanly has characterized the cholera everywhere. Intemperance is a qualification which it never overlooks. Often has it passed harmless over a wide population of temperate country people, and poured down, as an overflowing scourge, upon the drunkards of some distant town.” Says another English publication, “All experience, both in Great Britain and elsewhere, has proved that those who have been addicted to drinking spirituous liquors, and indulging in irregular habits, have been the greatest sufferers from cholera. In some towns the drunkards are all dead.” Rammohun Fingee, the famous Indian doctor, says, with regard to India, that people who do not take opium, or spirits, do not take this disorder even when they are with those who have it. Monsieur Huber, who saw 2,160 persons perish in twenty-five days in one town in Russia, says, “It is a most remarkable circumstance, that persons given to drinking have been swept away like flies. In Tiflis, containing 20,000 inhabitants, every drunkard has fallen—all are dead, not one remains.”

Dr. Sewall, of Washington city, in a letter from New York, states, that of 204 cases of cholera in the Park hospital, there were only six temperate persons, and that those had recovered; while 122 of the others, when he wrote, had died; and that the facts were similar in all the other hospitals.

In Albany, a careful examination was made by respectable gentlemen into the cases of those who died of the cholera in that city in 1832, over sixteen years of age. The[15, B] result was examined in detail by nine physicians, members of the medical staff attached to the board of health in that city—all who belong to it, except two, who were at that time absent—and published at their request under the signature of the Chancellor of the State, and the five distinguished gentlemen who compose the Executive Committee of the New York State Temperance Society, and is as follows: number of deaths, 366; viz. intemperate, 140; free drinkers, 55; moderate drinkers, mostly habitual, 131; strictly temperate, who drank no ardent spirits, 5; members of Temperance societies, 2; and when it is recollected that of more than 5,000 members of Temperance societies in the city of Albany, only two, not one in 2,500, fell by this disease, while it cut off more than one in fifty of the inhabitants of that city, we cannot but feel that men who furnish ardent spirit as a drink for their fellow-men, are manifestly inviting the ravages, and preparing the victims of this fatal malady, and of numerous other mortal diseases; and when inquisition is made for blood, and the effects of their employment are examined for the purpose of rendering to them according to their work, they will be found, should they continue, to be guilty of knowingly destroying their fellow-men.

What right have men, by selling ardent spirit, to increase the danger, extend the ravages, and augment and perpetuate the malignancy of the cholera, and multiply upon the community numerous other mortal diseases? Who cannot see that it is a foul, deep, and fatal injury inflicted on society? that it is in a high degree cruel and unjust? that it scatters the population of our cities, renders our business stagnant, and exposes our sons and our daughters to premature and sudden death? So manifestly is this the case, that the board of health of the city of Washington, on the approach of the cholera, declared the vending of ardent spirit, in any quantity, to be a nuisance; and, as such, ordered that it be discontinued for the space of ninety days. This was done in[16, B] self-defence, to save the community from the sickness and death which the vending of spirit is adapted to occasion. Nor is this tendency to occasion disease and death confined to the time when the cholera is raging.

By the statement of the physicians in Annapolis, Maryland, it appears that the average number of deaths by intemperance for several years, has been one to every 329 inhabitants; which would make in the United States 40,000 in a year. And it is the opinion of physicians, that as many more die of diseases which are induced, or aggravated, and rendered mortal by the use of ardent spirit. And to those results, all who make it, sell it, or use it, are accessory.

It is a principle in law, that the perpetrator of crime, and the accessory to it, are both guilty, and deserving of punishment. Men have been brought to the gallows on this principle. It applies to the law of God. And as the drunkard cannot go to heaven, can drunkard-makers? Are they not, when tried by the principles of the Bible, in view of the developments of Providence, manifestly immoral men? men who, for the sake of money, will knowingly be instrumental in corrupting the character, increasing the diseases, and destroying the lives of their fellow-men?

“But,” says one, “I never sell to drunkards; I sell only to sober men.” And is that any better? Is it a less evil to the community to make drunkards of sober men than it is to kill drunkards? Ask that widowed mother who did her the greatest evil: the man who only killed her drunken husband, or the man who made a drunkard of her only son? Ask those orphan children who did them the greatest injury: the man who made their once sober, kind, and affectionate father a drunkard, and thus blasted all their hopes, and turned their home, sweet home, into the emblem of hell; or the man who, after they had suffered for years the anguish, the indescribable anguish of the drunkard’s children, and seen their heart-broken mother[17, B] in danger of an untimely grave, only killed their drunken father, and thus caused in their habitation a great calm? Which of these two men brought upon them the greatest evil? Can you doubt? You, then, do nothing but make drunkards of sober men, or expose them to become such. Suppose that all the evils which you may be instrumental in bringing upon other children, were to come upon your own, and that you were to bear all the anguish which you may occasion; would you have any doubt that the man who would knowingly continue to be accessory to the bringing of these evils upon you, must be a notoriously wicked man?

5. Ardent spirit destroys the soul.

Facts in great numbers are now before the public, which show conclusively that the use of ardent spirit tends strongly to hinder the moral and spiritual illumination and purification of men; and thus to prevent their salvation, and bring upon them the horrors of the second death.

A disease more dreadful than the cholera, or any other that kills the body merely, is raging, and is universal, threatening the endless death of the soul. A remedy is provided all-sufficient, and infinitely efficacious; but the use of ardent spirit aggravates the disease, and with millions and millions prevents the application of the remedy and its effect.

It appears from the fifth report of the American Temperance Society, that more than four times as many, in proportion to the number, over wide regions of country, during the preceding year, have apparently embraced the gospel, and experienced its saving power, from among those who had renounced the use of ardent spirit, as from those who continued to use it.

The committee of the New York State Temperance Society, in view of the peculiar and unprecedented attention to religion which followed the adoption of the plan of abstinence from the use of strong drink, remark, that when[18, B] this course is taken, the greatest enemy to the work of the Holy Spirit on the minds and hearts of men, appears to be more than half conquered.

In three hundred towns, six-tenths of those who two years ago belonged to Temperance societies, but were not hopefully pious, have since become so; and eight-tenths of those who have within that time become hopefully pious, who did not belong to Temperance societies, have since joined them. In numerous places, where only a minority of the people abstained from the use of ardent spirit, nine-tenths of those who have of late professed the religion of Christ, have been from that minority. This is occasioned in various ways. The use of ardent spirit keeps many away from the house of God, and thus prevents them from coming under the sound of the gospel. And many who do come, it causes to continue stupid, worldly-minded, and unholy. A single glass a day is enough to keep multitudes of men, under the full blaze of the gospel, from ever experiencing its illuminating and purifying power. Even if they come to the light, and it shines upon them, it shines upon darkness, and the darkness does not comprehend it; while multitudes who thus do evil will not come to the light, lest their deeds should be reproved. There is a total contrariety between the effect produced by the Holy Spirit, and the effect of spirituous liquor upon the minds and hearts of men. The latter tends directly and powerfully to counteract the former. It tends to make men feel in a manner which Jesus Christ hates, rich spiritually, increased in goods, and in need of nothing; while it tends for ever to prevent them from feeling, as sinners must feel, to buy of him gold tried in the fire, that they may be rich. Those who use it, therefore, are taking the direct course to destroy their own souls; and those who furnish it, are taking the course to destroy the souls of their fellow-men.

In one town, more than twenty times as many, in proportion[19, B] to the number, professed the religion of Christ during the past year, of those who did not use ardent spirit, as of those who did; and in another town more than thirty times as many. In other towns, in which from one-third to two-thirds of the people did not use it, and from twenty to forty made a profession of religion, they were all from the same class. What, then, are those men doing who furnish it, but taking the course which is adapted to keep men stupid in sin till they sink into the agonies of the second death? And is not this an immorality of a high and aggravated description? and one which ought to mark every man who understands its nature and effects, and yet continues to live in it, as a notoriously immoral man? What though he does not live in other immoralities—is not this enough? Suppose he should manufacture poisonous miasma, and cause the cholera in our dwellings; sell, knowingly, the cause of disease, and increase more than one-fifth over wide regions of country the number of adult deaths, would he not be a murderer? “I know,” says the learned Judge Crunch, “that the cup” which contains ardent spirit “is poisoned; I know that it may cause death, that it may cause more than death, that it may lead to crime, to sin, to the tortures of everlasting remorse. Am I not, then, a murderer? worse than a murderer? as much worse as the soul is better than the body? If ardent spirits were nothing worse than a deadly poison—if they did not excite and inflame all the evil passions—if they did not dim that heavenly light which the Almighty has implanted in our bosoms to guide us through the obscure passages of our pilgrimage—if they did not quench the Holy Spirit in our hearts, they would be comparatively harmless. It is their moral effect—it is the ruin of the soul which they produce, that renders them so dreadful. The difference between death by simple poison, and death by habitual intoxication, may extend to the whole difference between everlasting happiness and eternal death.”

And, say the New York State Society, at the head of which is the Chancellor of the State, “Disguise that business as they will, it is still, in its true character, the business of destroying the bodies and souls of men. The vender and the maker of spirits, in the whole range of them, from the pettiest grocer to the most extensive distiller, are fairly chargeable, not only with supplying the appetite for spirits, but with creating that unnatural appetite; not only with supplying the drunkard with the fuel of his vices, but with making the drunkard.

“In reference to the taxes with which the making and vending of spirits loads the community, how unfair towards others is the occupation of the maker and vender of them! A town, for instance, contains one hundred drunkards. The profit of making these drunkards is enjoyed by some half a dozen persons; but the burden of these drunkards rests upon the whole town. We do not suggest that there should be such a law, but we ask whether there would be one law in the whole statute-book more righteous than that which should require those who have the profit of making our drunkards to be burdened with the support of them.”

Multitudes who once cherished the fond anticipation of happiness in this life and that to come, there is reason to believe, are now wailing beyond the reach of hope, through the influence of ardent spirit; and multitudes more, if men continue to furnish it as a drink, especially sober men, will go down to weep and wail with them to endless ages.

“But,” says one, “the traffic in ardent spirit is a lawful business; it is approbated by law, and is therefore right.” But the keeping of gambling houses is, in some cases, approbated by human law. Is that therefore right? The keeping of brothels is, in some cases, approbated by law. Is that therefore right? Is it human law that is the standard of morality and religion? May not a man be a notoriously[21, B] wicked man, and yet not violate human law? The question is, Is it right? Does it accord with the divine law? Does it tend in its effects to bring glory to God in the highest, and to promote the best good of mankind? If not, the word of God forbids it; and if a man who has the means of understanding its nature and effects continues to follow it, he does it at the peril of his soul.

“But,” says another, “if I should not sell it, I could not sell so many other things.” If you could not, then you are forbidden by the word of God to sell so many other things. And if you continue to make money by that which tends to destroy your fellow-men, you incur the displeasure of Jehovah. “But if I should not sell it, I must change my business.” Then you are required by the Lord to change your business. A voice from the throne of his excellent glory cries, “Turn ye, turn ye from this evil way; for why will ye die?”

“If I should turn from it, I could not support my family.” This is not true; at least, no one has a right to say that it is true till he has tried it, and done his whole duty by ceasing to do evil and learning to do well, trusting in God, and has found that his family is not supported. Jehovah declares, that such as seek the Lord, and are governed by his will, shall not want any good thing. And till men have made the experiment of obeying him in all things, and found that they cannot support their families, they have no right to say that it is necessary for them to sell ardent spirit. And if they do say this, it is a libel on the divine character and government. There is no truth in it. He who feeds the sparrow and clothes the lily, will, if they do right, provide for them and their families; and there is no shadow of necessity, in order to obtain support, for them to carry on a business which destroys their fellow-men.

“But others will do it, if I do not.” Others will send out their vessels, steal the black man, and sell him and his[22, B] children into perpetual bondage, if you do not. Others will steal, rob, and commit murder, if you do not; and why may not you do it, and have a portion of the profit, as well as they? Because, if you do, you will be a thief, a robber, and a murderer, like them. You will here be partaker of their guilt, and hereafter of their plagues. Every friend, therefore, to you, to your Maker, or the eternal interests of men, will, if acquainted with this subject, say to you, As you value the favor of God, and would escape his righteous and eternal indignation, renounce this work of death; for he that soweth death, shall also reap death.

“But our fathers imported, manufactured, and sold ardent spirit, and were they not good men? Have not they gone to heaven?” Men who professed to be good once had a multiplicity of wives, and have not some of them too gone to heaven? Men who professed to be good once were engaged in the slave-trade, and have not some of them gone to heaven? But can men who understand the will of God with regard to these subjects, continue to do such things now, and yet go to heaven? The principle which applies in this case, and which makes the difference between those who did such things once, and those who continue to do them now, is that to which Jesus Christ referred when he said, “If I had not come and spoken to them, they had not had sin; but now they have no cloak for their sin.” The days of that darkness and ignorance which God may have winked at have gone by, and he now commandeth all men to whom his will is made known to repent. Your fathers, when they were engaged in selling ardent spirit, did not know that all men, under all circumstances, would be better without it. They did not know that it caused three-quarters of the pauperism and crime in the land—that it deprived many of reason—greatly increased the number and severity of diseases, and brought down such multitudes to an untimely grave. The facts had not then been collected and published. They did[23, B] not know that it tended so fatally to obstruct the progress of the Gospel, and ruin, for eternity, the souls of men. You do know it, or have the means of knowing it. You cannot sin with as little guilt as did your fathers. The facts, which are the voice of God in his providence, and manifest his will, are now before the world. By them he has come and spoken to you. And if you continue, under these circumstances, to violate his will, you will have no cloak, no covering, no excuse for your sin. And though sentence against this evil work is not executed at once, judgment, if you continue, will not linger, nor will damnation slumber.

The accessory and the principal, in the commission of crime, are both guilty. Both by human laws are condemned. The principle applies to the law of God; and not only drunkards, but drunkard-makers—not only murderers, but those who excite others to commit murder, and furnish them with the known cause of their evil deeds, will, if they understand what they do, and continue thus to rebel against God, be shut out of heaven.

Among the Jews, if a man had a beast that went out and killed a man, the beast, said Jehovah, shall be slain, and his flesh shall not be eaten. The owner must lose the whole of him as a testimony to the sacredness of human life, and a warning to all not to do any thing, or connive at any thing that tended to destroy it. But the owner, if he did not know that the beast was dangerous, and liable to kill, was not otherwise to be punished. But if he did know, if it had been testified to the owner that the beast was dangerous, and liable to kill, and he did not keep him in, but let him go out, and he killed a man, then, by the direction of Jehovah, the beast and the owner were both to be put to death. The owner, under these circumstances, was held responsible, and justly too, for the injury which his beast might do. Though men are not required or permitted now to execute this law, as they were when God was the Magistrate, yet the reason of[24, B] the law remains. It is founded in justice, and is eternal. To the pauperism, crime, sickness, insanity, and death temporal and eternal, which ardent spirit occasions, those who knowingly furnish the materials, those who manufacture, and those who sell it, are all accessory, and as such will be held responsible at the divine tribunal. There was a time when the owners did not know the dangerous and destructive qualities of this article—when the facts had not been developed and published, nor the minds of men turned to the subject; when they did not know that it caused such a vast portion of the vice and wretchedness of the community, and such wide-spreading desolation to the temporal and eternal interests of men; and although it then destroyed thousands, for both worlds, the guilt of the men who sold it was comparatively small. But now they sin against light, pouring down upon them with unutterable brightness; and if they know what they do, and in full view of its consequences continue that work of death—not only let the poison go out, but furnish it, and send it out to all who are disposed to purchase—it had been better for them, and better for many others, if they had never been born. For, briefly to sum up what we have said,

1. It is the selling of that, without the use of which nearly all the business of this world was conducted, till within less than three hundred years, and which of course is not needful.

2. It is the selling of that which was not generally used by the people of this country for more than a hundred years after the country was settled, and which by hundreds of thousands, and some in all kinds of lawful business, is not used now. Once they did use it, and thought it needful or useful. But by experiment, the best evidence in the world, they have found that they were mistaken, and that they are in all respects better without it. And the cases are so numerous as to make it certain, that should the experiment be[25, B] fairly made, this would be the case with all. Of course it is not useful.

3. It is the selling of that which is a real, a subtile and very destructive poison—a poison which, by men in health, cannot be taken without deranging healthy action, and inducing more or less disease, both of body and mind; which is, when taken in any quantity, positively hurtful; and which is of course forbidden by the word of God.

4. It is the selling of that which tends to form an unnatural, and a very dangerous and destructive appetite; which, by gratification, like the desire of sinning in the man who sins, tends continually to increase, and which thus exposes all who form it to come to a premature grave.

5. It is the selling of that which causes a great portion of all the pauperism in our land; and thus, for the benefit of a few—those who sell—brings an enormous tax on the whole community. Is this fair? Is it just? Is it not exposing our children and youth to become drunkards? And is it not inflicting great evils on society?

6. It is the selling of that which excites to a great portion of all the crimes that are committed, and which is thus shown to be in its effects hostile to the moral government of God, and to the social, civil, and religious interests of men; at war with their highest good, both for this life and the life to come.

7. It is the selling of that, the sale and use of which, if continued, will form intemperate appetites, which, if formed, will be gratified, and thus will perpetuate intemperance and all its abominations to the end of the world.

8. It is the selling of that which makes wives widows, and children orphans; which leads husbands often to murder their wives, and wives to murder their husbands; parents to murder their children, and children to murder their parents; and which prepares multitudes for the prison, for the gallows, and for hell.

9. It is the selling of that which greatly increases the amount and severity of sickness; which in many cases destroys reason; which causes a great portion of all the sudden deaths, and brings down multitudes who were never intoxicated, and never condemned to suffer the penalty of the civil law, to an untimely grave.

10. It is the selling of that which tends to lessen the health, the reason, and the usefulness, to diminish the comfort, and shorten the lives of all who habitually use it.

11. It is the selling of that which darkens the understanding, sears the conscience, pollutes the affections, and debases all the powers of man.

12. It is the selling of that which weakens the power of motives to do right, and increases the power of motives to do wrong, and is thus shown to be in its effects hostile to the moral government of God, as well as to the temporal and eternal interests of men; which excites men to rebel against him, and to injure and destroy one another. And no man can sell it without exerting an influence which tends to hinder the reign of the Lord Jesus Christ over the minds and hearts of men, and to lead them to persevere in iniquity, till, notwithstanding all the kindness of Jehovah, their case shall become hopeless.

Suppose a man, when about to commence the traffic in ardent spirit, should write in great capitals on his sign-board, to be seen and read of all men, what he will do, viz., that so many of the inhabitants of this town or city, he will, for the sake of getting their money, make paupers, and send them to the almshouse, and thus oblige the whole community to support them and their families; that so many others he will excite to the commission of crimes, and thus increase the expenses, and endanger the peace and welfare of the community; that so many he will send to the jail, and so many more to the state prison, and so many to the gallows;[27, B] that so many he will visit with sore and distressing diseases; and in so many cases diseases which would have been comparatively harmless, he will by his poison render fatal; that in so many cases he will deprive persons of reason, and in so many cases will cause sudden death; that so many wives he will make widows, and so many children he will make orphans, and that in so many cases he will cause the children to grow up in ignorance, vice, and crime, and after being nuisances on earth, will bring them to a premature grave; that in so many cases he will prevent the efficacy of the Gospel, grieve away the Holy Ghost, and ruin for eternity the souls of men. And suppose he could, and should give some faint conception of what it is to lose the soul, and of the overwhelming guilt and coming wretchedness of him who is knowingly instrumental in producing this ruin; and suppose he should put at the bottom of the sign this question, viz., What, you may ask, can be my object in acting so much like a devil incarnate, and bringing such accumulated wretchedness upon a comparatively happy people? and under it should put the true answer, money; and go on to say, I have a family to support; I want money, and must have it; this is my business, I was brought up to it; and if I should not follow it I must change my business, or I could not support my family. And as all faces begin to gather blackness at the approaching ruin, and all hearts to boil with indignation at its author, suppose he should add for their consolation, “If I do not bring this destruction upon you, somebody else will.” What would they think of him? what would all the world think of him? what ought they to think of him? And is it any worse for a man to tell the people beforehand honestly what he will do, if they buy and use his poison, than it is to go on and do it? And what if they are not aware of the mischief which he is doing them, and he can accomplish it through their own perverted and voluntary agency? Is it[28, B] not equally abominable, if he knows it, and does not cease from producing it?

And if there are churches whose members are doing such things, and those churches are not blessed with the presence and favor of the Holy Ghost, they need not be at any loss for the reason. And if they should never again, while they continue in this state, be blessed with the reviving influence of God’s Spirit, they need not be at any loss for the reason. Their own members are exerting a strong and fatal influence against it; and that too after Divine Providence has shown them what they are doing. And in many such cases there is awful guilt with regard to this thing resting upon the whole church. Though they have known for years what these men were doing; have seen the misery, heard the oaths, witnessed the crimes, and known the wretchedness and deaths which they have occasioned, and perhaps have spoken of it, and deplored it among one another; many of them have never spoken on this subject to the persons themselves. They have seen them scattering firebrands, arrows, and death temporal and eternal, and yet have never so much as warned them on the subject, and never besought them to give up their work of death.

An individual lately conversed with one of his professed Christian brethren who was engaged in this traffic, and told him not only that he was ruining for both worlds many of his fellow-men, but that his Christian brethren viewed his business as inconsistent with his profession, and tending to counteract all efforts for the salvation of men; and the man, after frankly acknowledging that it was wrong, said that this was the first time that any of them had conversed with him on the subject. This may be the case with other churches; and while it is, the whole church is conniving at the evil, and the whole church is guilty. Every brother, in such a case, is bound, on his own account, to converse with him who is thus aiding the powers[29, B] of darkness, and opposing the kingdom of Jesus Christ, and try to persuade him to cease from this destructive business.

The whole church is bound to make efforts, and use all proper means to accomplish this result. And before half the individual members have done their duty on this subject, they may expect, if the offending brother has, and manifests the spirit of Christ, that he will cease to be an offence to his brethren, and a stumbling-block to the world, over which such multitudes fall to the pit of woe. And till the church, the whole church, do their duty on this subject, they cannot be freed from the guilt of conniving at the evil. And no wonder if the Lord leaves them to be as the mountains of Gilboa, on which there was neither rain or dew. And should the church receive from the world those who make it a business to carry on this notoriously immoral traffic, they will greatly increase their guilt, and ripen for the awful displeasure of God. And unless members of the church shall cease to teach, by their business, the fatal error that it is right for men to buy and use ardent spirit as a drink, the evil will never be eradicated, intemperance will never cease, and the day of millennial glory never come.

Each individual who names the name of Christ is called upon, by the providence of God, to act on this subject openly and decidedly for him, and in such a manner as is adapted to banish intemperance and all its abominations from the earth, and to cause temperance and all its attendant benefits universally to prevail. And if ministers of the Gospel and members of Christian churches do not connive at the sin of furnishing this poison as a drink for their fellow-men; and men who, in opposition to truth and duty, continue to be engaged in this destructive employment, are viewed and treated as wicked men; the work which the Lord hath commenced and carried forward with a rapidity, and to an extent hitherto unexampled in the history of the world, will continue to move onward till not a name, nor a trace, nor a[30, B] shadow of a drunkard, or a drunkard-maker, shall be found on the globe.

Professed Christian—In the manufacture or sale of ardent spirit as a drink, you do not, and you cannot honor God; but you do, and, so long as you continue it, you will greatly dishonor Him. You exert an influence which tends directly and strongly to ruin, for both worlds, your fellow-men. Should you take a quantity of that poisonous liquid into your closet, present it before the Lord, confess to him its nature and effects, spread out before him what it has done and what it will do, and attempt to ask him to bless you in extending its influence; it would, unless your conscience is already seared as with a hot iron, appear to you like blasphemy. You could no more do it than you could take the instruments of gambling and attempt to ask God to bless you in extending them through the community. And why not, if it is a lawful business? Why not ask God to increase it, and make you an instrument in extending it over the country, and perpetuating it to all future generations? Even the worldly and profane man, when he hears about professing Christians offering prayer to God that he would bless them in the manufacture or sale of ardent spirit, involuntarily shrinks back and says, “That is too bad.” He can see that it is an abomination. And if it is too bad for a professed Christian to pray about it, is it not too bad for him to practise it? If you continue, under all the light which God in his providence has furnished with regard to its hurtful nature and destructive effects, to furnish ardent spirit as a drink for your fellow-men, you will run the fearful hazard of losing your soul, and you will exert an influence which powerfully tends to destroy the souls of your fellow-men. Every time you furnish it you are rendering it less likely that they will be illuminated, sanctified, and saved, and more likely that they will continue in sin and go down to the chambers of death.

It is always worse for a church-member to do an immoral act, and teach an immoral sentiment, than for an immoral man, because it does greater mischief. And this is understood, and often adverted to by the immoral themselves. Even drunkards are now stating it to their fellow-drunkards, that church-members are not better than they. And to prove it, are quoting the fact, that although they are not drunkards, and perhaps do not get drunk, they, for the sake of money, carry on the business of making drunkards. And are not the men and their business of the same character? “The deacon,” says a drunkard, “will not use ardent spirit himself: he says, ‘It is poison!’ But for six cents he will sell it to me. And though he will not furnish it to his own children, for he says, ‘It will ruin them!’ yet he will furnish it to mine. And there is my neighbor, who was once as sober as the deacon himself, but he had a pretty farm, which the deacon wanted, and for the sake of getting it he has made him a drunkard. And his wife, as good a woman as ever lived, has died of a broken heart, because her children would follow their father.” No, you cannot convince even a drunkard, that the man who is selling him that which he knows is killing him, is any better than the drunkard himself. Nor can you convince a sober man, that he who, for the sake of money, will, with his eyes open, make drunkards of sober men, is any less guilty than the drunkards he makes.