PREFACE.

The aim of this work has been to sketch the various periods and styles of architecture with the broadest possible strokes, and to mention, with such brief characterization as seemed permissible or necessary, the most important works of each period or style. Extreme condensation in presenting the leading facts of architectural history has been necessary, and much that would rightly claim place in a larger work has been omitted here. The danger was felt to be rather in the direction of too much detail than of too little. While the book is intended primarily to meet the special requirements of the college student, those of the general reader have not been lost sight of. The majority of the technical terms used are defined or explained in the context, and the small remainder in a glossary at the end of the work. Extended criticism and minute description were out of the question, and discussion of controverted points has been in consequence as far as possible avoided.

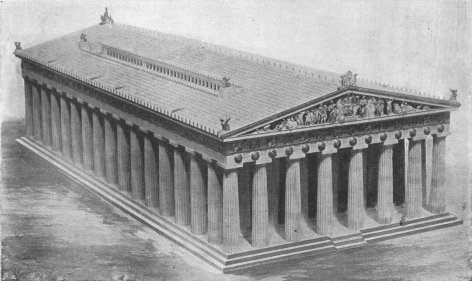

The illustrations have been carefully prepared with a view to elucidating the text, rather than for pictorial effect. With the exception of some fifteen cuts reproduced from Lübke’s Geschichte der Architektur (by kind permission of Messrs. Seemann, of Leipzig), the illustrations are almost all entirely new. A large number are from vi original drawings made by myself, or under my direction, and the remainder are, with a few exceptions, half-tone reproductions prepared specially for this work from photographs in my possession. Acknowledgments are due to Messrs. H. W. Buemming, H. D. Bultman, and A. E. Weidinger for valued assistance in preparing original drawings; and to Professor W. R. Ware, to Professor W. H. Thomson, M.D., and to the Editor of the Series for much helpful criticism and suggestion.

It is hoped that the lists of monuments appended to the history of each period down to the present century may prove useful for reference, both to the student and the general reader, as a supplement to the body of the text.

A. D. F. Hamlin.

Columbia College, New York,

January 20, 1896.

The author desires to express his further acknowledgments to the friends who have at various times since the first appearance of this book called his attention to errors in the text or illustrations, and to recent advances in the art or in its archæology deserving of mention in subsequent editions. As far as possible these suggestions have been incorporated in the various revisions and reprints which have appeared since the first publication.

A. D. F. H.

Columbia University,

October 28, 1907.

GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY.

(This includes the leading architectural works treating of more than one period or style. The reader should consult also the special references at the head of each chapter. Valuable material is also contained in the leading architectural periodicals and in monographs too numerous to mention.)

Dictionaries and Encyclopedias.

Agincourt, History of Art by its Monuments; London.

Architectural Publication Society, Dictionary of Architecture; London.

Bosc, Dictionnaire raisonné d’architecture; Paris.

Durm and others, Handbuch der Architektur; Stuttgart. (This is an encyclopedic compendium of architectural knowledge in many volumes; the series not yet complete. It is referred to as the Hdbuch. d. Arch.)

Gwilt, Encyclopedia of Architecture; London.

Longfellow and Frothingham, Cyclopedia of Architecture in Italy and the Levant; New York.

Planat, Encyclopédie d’architecture; Paris.

Sturgis, Dictionary of Architecture and Building; New York.

General Handbooks and Histories.

Bühlmann, Die Architektur des klassischen Alterthums und der Renaissance; Stuttgart. (Also in English, published in New York.)

Choisy, Histoire de l’architecture; Paris.

Durand, Recueil et parallèle d’édifices de tous genres; Paris.

Fergusson, History of Architecture in All Countries; London.

Fletcher and Fletcher, A History of Architecture; London.

xxGailhabaud, L’Architecture du Vme. au XVIIIme. siècle; Paris.—Monuments anciens et modernes; Paris.

Kugler, Geschichte der Baukunst; Stuttgart.

Longfellow, The Column and the Arch; New York.

Lübke, Geschichte der Architektur; Leipzig.—History of Art, tr. and rev. by R. Sturgis; New York.

Perry, Chronology of Mediæval and Renaissance Architecture; London.

Reynaud, Traité d’architecture; Paris.

Rosengarten, Handbook of Architectural Styles; London and New York.

Simpson, A History of Architectural Development; London.

Spiers, Architecture East and West; London.

Stratham, Architecture for General Readers; London.

Sturgis, European Architecture; New York.

Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects; London.

Viollet-le-Duc, Discourses on Architecture; Boston.

Theory, the Orders, etc.

Chambers, A Treatise on Civil Architecture; London.

Daviler, Cours d’architecture de Vignole; Paris.

Esquié, Traité élémentaire d’architecture; Paris.

Guadet, Théorie de l’architecture; Paris.

Robinson, Principles of Architectural Composition; New York.

Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture; London.

Sturgis, How to Judge Architecture; New York.

Tuckerman, Vignola, the Five Orders of Architecture; New York.

Van Brunt, Greek Lines and Other Essays; Boston.

Van Pelt, A Discussion of Composition.

Ware, The American Vignola; Scranton.

xxiHISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE.

INTRODUCTION.

A history of architecture is a record of man’s efforts to build beautifully. The erection of structures devoid of beauty is mere building, a trade and not an art. Edifices in which strength and stability alone are sought, and in designing which only utilitarian considerations have been followed, are properly works of engineering. Only when the idea of beauty is added to that of use does a structure take its place among works of architecture. We may, then, define architecture as the art which seeks to harmonize in a building the requirements of utility and of beauty. It is the most useful of the fine arts and the noblest of the useful arts. It touches the life of man at every point. It is concerned not only in sheltering his person and ministering to his comfort, but also in providing him with places for worship, amusement, and business; with tombs, memorials, embellishments for his cities, and other structures for the varied needs of a complex civilization. It engages the services of a larger portion of the community and involves greater outlays of money than any other occupation except agriculture. Everyone at some point comes in contact with the work of the architect, and from this universal contact architecture derives its significance as an index of the civilization of an age, a race, or a people.

xxiiIt is the function of the historian of architecture to trace the origin, growth, and decline of the architectural styles which have prevailed in different lands and ages, and to show how they have reflected the great movements of civilization. The migrations, the conquests, the commercial, social, and religious changes among different peoples have all manifested themselves in the changes of their architecture, and it is the historian’s function to show this. It is also his function to explain the principles of the styles, their characteristic forms and decoration, and to describe the great masterpieces of each style and period.

STYLE is a quality; the “historic styles” are phases of development. Style is character expressive of definite conceptions, as of grandeur, gaiety, or solemnity. An historic style is the particular phase, the characteristic manner of design, which prevails at a given time and place. It is not the result of mere accident or caprice, but of intellectual, moral, social, religious, and even political conditions. Gothic architecture could never have been invented by the Greeks, nor could the Egyptian styles have grown up in Italy. Each style is based upon some fundamental principle springing from its surrounding civilization, which undergoes successive developments until it either reaches perfection or its possibilities are exhausted, after which a period of decline usually sets in. This is followed either by a reaction and the introduction of some radically new principle leading to the evolution of a new style, or by the final decay and extinction of the civilization and its replacement by some younger and more virile element. Thus the history of architecture appears as a connected chain of causes and effects succeeding each other without break, each style growing out of that which preceded it, or springing out of the fecundating contact of a higher with a lower civilization. To study architectural styles is therefore to study a branch of the history of civilization.

xxiiiTechnically, architectural styles are identified by the means they employ to cover enclosed spaces, by the characteristic forms of the supports and other members (piers, columns, arches, mouldings, traceries, etc.), and by their decoration. The plan should receive special attention, since it shows the arrangement of the points of support, and hence the nature of the structural design. A comparison, for example, of the plans of the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (Fig. 11, h) and of the Basilica of Constantine (Fig. 58) shows at once a radical difference in constructive principle between the two edifices, and hence a difference of style.

STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES. All architecture is based on one or more of three fundamental structural principles; that of the lintel, of the arch or vault, and of the truss. The principle of the lintel is that of resistance to transverse strains, and appears in all construction in which a cross-piece or beam rests on two or more vertical supports. The arch or vault makes use of several pieces to span an opening between two supports. These pieces are in compression and exert lateral pressures or thrusts which are transmitted to the supports or abutments. The thrust must be resisted either by the massiveness of the abutments or by the opposition to it of counter-thrusts from other arches or vaults. Roman builders used the first, Gothic builders the second of these means of resistance. The truss is a framework so composed of several pieces of wood or metal that each shall best resist the particular strain, whether of tension or compression, to which it is subjected, the whole forming a compound beam or arch. It is especially applicable to very wide spans, and is the most characteristic feature of modern construction. How the adoption of one or another of these principles affected the forms and even the decoration of the various styles, will be shown in the succeeding chapters.

HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT. Geographically and chronologically, architecture appears to have originated in the Nile xxiv valley. A second centre of development is found in the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, not uninfluenced by the older Egyptian art. Through various channels the Greeks inherited from both Egyptian and Assyrian art, the two influences being discernible even through the strongly original aspect of Greek architecture. The Romans in turn, adopting the external details of Greek architecture, transformed its substance by substituting the Etruscan arch for the Greek construction of columns and lintels. They developed a complete and original system of construction and decoration and spread it over the civilized world, which has never wholly outgrown or abandoned it.

With the fall of Rome and the rise of Constantinople these forms underwent in the East another transformation, called the Byzantine, in the development of Christian domical church architecture. In the North and West, meanwhile, under the growing institutions of the papacy and of the monastic orders and the emergence of a feudal civilization out of the chaos of the Dark Ages, the constant preoccupation of architecture was to evolve from the basilica type of church a vaulted structure, and to adorn it throughout with an appropriate dress of constructive and symbolic ornament. Gothic architecture was the outcome of this preoccupation, and it prevailed throughout northern and western Europe until nearly or quite the close of the fifteenth century.

During this fifteenth century the Renaissance style matured in Italy, where it speedily triumphed over Gothic fashions and produced a marvellous series of civic monuments, palaces, and churches, adorned with forms borrowed or imitated from classic Roman art. This influence spread through Europe in the sixteenth century, and ran a course of two centuries, after which a period of servile classicism was followed by a rapid decline in taste. To this succeeded the eclecticism and confusion of the nineteenth century, to xxv which the rapid growth of new requirements and development of new resources have largely contributed.

In Eastern lands three great schools of architecture have grown up contemporaneously with the above phases of Western art; one under the influence of Mohammedan civilization, another in the Brahman and Buddhist architecture of India, and the third in China and Japan. The first of these is the richest and most important. Primarily inspired from Byzantine art, always stronger on the decorative than on the constructive side, it has given to the world the mosques and palaces of Northern Africa, Moorish Spain, Persia, Turkey, and India. The other two schools seem to be wholly unrelated to the first, and have no affinity with the architecture of Western lands.

Of Mexican, Central American, and South American architecture so little is known, and that little is so remote in history and spirit from the styles above enumerated, that it belongs rather to archæology than to architectural history, and will not be considered in this work.

Note.—The reader’s attention is called to the Appendix to this volume, in which are gathered some of the results of recent investigations and of the architectural progress of the last few years which could not readily be introduced into the text of this edition. The General Bibliography and the lists of books recommended have been revised and brought up to date.